MUTATING THROUGH TIME

This article is the last in the series “På sporet af Kunsten” and the first one written in English. “På sporet af Kunsten” was a travel diary reporting from different exhibitions around Denmark last Summer. A way of mapping my own homeland after having spent years and years traveling abroad. With the intention to broaden my Danish network of colleagues and create new connections for possible future collaborations, I ended up discovering not only a lot of beautiful and inspiring art but also a whole new way of being with myself as I believe slow travel have always influenced people’s bodies and mind in incomparable ways. I wrote about this transformative aspect in the article “At netværke med navlen” inspired by Neimanis’ hydrofeminist reflections on morning sickness, gut feelings, bellybutton communication and other navel gazing insights.

This text is to be read as a continuation of my previous articles on idoart.dk and concerns the fermentation of data, using time, technology, matter and microbiology as common tools of telling and transforming.

A blind passenger

During my journey in August, I excavated my own future, using a modern-day version of the ancient frog method, in which women used to pee on the amphibian, to test their urine of a certain bacteria. Purchased in an un-charming, suburban supermarket, a simple pregnancy test revealed the fermentation process taking place inside my body.

As a fortune teller, that little chemical reaction on the cotton swab, told me which direction my life was about to take. I cannot describe how surreal this felt. It is the craziest thing I’ve ever experienced, and the realization of hosting all these new cells, bacteria and whatever else it takes to grow new life, is still one big mystery to me. Yet it is the most bodily “out-of-the-body” experience I have hitherto had, and probably the closest I will ever get to understanding fermentation of the human data we call DNA.

“I cannot describe how surreal this felt. It is the craziest thing I’ve ever experienced, and the realization of hosting all these new cells, bacteria and whatever else it takes to grow new life, is still one big mystery to me. ”

Becoming aware of my blind passenger made me divert from the planned route and return to Copenhagen to share the news with my partner. I therefore decided to go back to Aarhus some months later, since this was the last place on my trip, which I’d had to skip in August.

In the meantime, I was obviously occupied with trying to grasp my new existence as a container of a yet unborn tiny new life. In her book “et hjerte i alt” Amalie Smith writes about the etymological origin of the word “material”, and concludes that mother and matter must share their roots in the Latin “mater” because both holds inherent the ability of creating offspring; giving birth to new matter. While we also know that curating is another word for caretaking, I’d like to suggest my new profession as mother and curator as a full-time care-worker. I care about the arts; I care for the planet and I practice selfcare as a daily exercise; to prepare myself for the soon to be and rest of my life most important task, that is taking care of my child.

But also, as an act of resistance to the white west patriarchal and capitalist driven society that tends to exhaust us in (re-)productivity, efficiency and performativity. Warmly inspired by The Nap Ministry I try to relax as much as possible these days and simply allow my body to grow and restore after 30 years of running towards something I never knew what was, but a society created convention telling me that happiness could only be obtained through material wealth, social status and career related success.

“Ever since I exchanged my mindset of labour with thoughts of going into labour, I must admit that writing an article like this (viewing and reviewing art in general) has not been easy.”

Ever since I exchanged my mindset of labour with thoughts of going into labour, I must admit that writing an article like this (viewing and reviewing art in general) has not been easy. Nevertheless, here is my best attempt. On the following pages I will take you through three exhibitions from the autumn in Aarhus: Sif Itona Westerberg at ARoS, Sissel Marie Tonn at Spanien19c and Anders Visti at Andromeda8220.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial. ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Immemorial: extemporary hybrids and cyborgs

Sif Itona Westerberg births her sculptures by hand carving mutations from the cheap industrial material aircrete. She transforms creatures from Greek mythology into gender liquid, eco-oriented and symbiotic hybrids of flora, fauna and Godlike cyborgs. Entering Sif’s solo show at ARoS, the story begins with the YOLO-lifestyle á la Dionysos’ overconsumption of pleasure and parties, which the past couple of Western world generations have enjoyed, before the current generation of young climate activists took over the stage. In the following room, we are presented with the son of the Sun God Helios. The artist here re-tells the story of Phaeton’s disastrous ride in his father’s chariot, which went out of control and burned the Earth in a manner similar to the human-caused global warming we know of today.

“Apparently, the curatorial intention here is to show Phaeton’s overconfident, narcissistic and self-destructive destiny as a possible first mover of the manmade environmental crisis, currently causing the sixth mass extinction on the planet, we all call home.”

Apparently, the curatorial intention here is to show Phaeton’s overconfident, narcissistic and self-destructive destiny as a possible first mover of the manmade environmental crisis, currently causing the sixth mass extinction on the planet, we all call home. Instead of depicting the protagonist himself, we see his sisters, whose grief over their stupid brother turned their tears into amber and the nymphs into poplar trees. I like to think about mankind’s transformation into trees and other beings while we extinct ourselves.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

In the third room, presented as the final act of the so-called “sculptural static theatre”, I am happy to revisit “The Fountain”, which I first encountered at Tranen a few years ago. This is where the artist reminds us, that humans playing God-tricks are no longer just a myth and neither is it purely sci-fi:

“In the USA, researchers have injected sheep embryos with human cells with the declared goal of growing human organs for transplantation. In China, monkey brains have been enriched with human brain cells – an experiment whose purpose critics question. CRISPR gene editing, which allows for cutting and pasting DNA strings, is but one among other new technologies that open up vast possibilities of manipulation of existing fauna and flora. […] The water is collected in tubs of polyester, which contain fabricated deposits of trilobites extinct 252 million years ago next to scientific visualization models of DNA strings.”

Thus introduces the director of Tranen, Toke Lykkeberg, the work of Sif Itona Westerberg he exhibited back in 2019, long before mutations were on everybody’s lips and tongues, bodies and minds.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Sif Itona Westerberg, Immemorial (Installation view). ARoS, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Digital and animal heartbeats – what keeps us alive?

Now, three years later, the first man has successfully received a genetically modified pig’s heart through a medical transplantation which saved his life. In the days following, different questions of ethics were raised: Is it okay to farm pigs as spare parts for defect human organs? Was the man who got the pig heart even worthy of living after having stabbed another man back in 1988? To what extent shall our past determine present, and how long into our future will our presence come to influence? Toke has written a very interesting article for Kunstkritikk discussing the collapse of time as we know it; an implosion of time which he termed “extemporary”; a tendency in the arts completely detached from the grand narrative of progress.

“Time is something we try to outrun even as we run out of it” he writes, and points to the way artists today examine different temporalities besides the human-centred only. To bridge the hybrid creatures of Sif Itona Westerberg with Sissel Marie Tonn’s fermentation of data, please allow me to introduce the manga cyborg Major from “Ghost in the shell” and her sister from another mister; Ann Lee who was born by the French artists Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno under the title “No ghost just a shell”. Their digital roots are what matters, while we keep in mind the man with the pig heart.

Both Major and Ann Lee have feelings, thoughts and memory – but no physical human heart, only a digital one keeps them alive. So, what does this ‘digital’ even mean? A little fun-fact here is that Digitalis is actually the name of a plant, from which the extract is used for curing heart failure. The plant can however, in certain dosage, cause heart failure.

“A little fun-fact here is that Digitalis is actually the name of a plant, from which the extract is used for curing heart failure. The plant can however, in certain dosage, cause heart failure.”

Being both medicine and poison a digital heart may sound poetic on one hand and ethically troublesome on the other. But to go a little further; I’d like to ask more broadly (or more specifically if you like): what keeps us alive? What makes us living beings besides the oxygen we share among us? To understand life, I search for answers in death:

Specialist in programmed cell death Jean Claude Ameisen suggests that Ann Lee (a manga character purchased from a catalogue and given identity by the artists’ storytelling) is alive due to her dependance on the artists and the audience. In a conversation about Ann Lee with Philippe Parreno and Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ameisen says:

“In the absence of partners, it can interact with, life is impossible. Life is collective; without interdependence there is no life.”

The “it” that dies without the collective refers not (merely) to the digital Ann Lee, but to all non-digital, biological cells. He supports his explanation with a newborn’s dependency of relationships and the impossibility to survive alone:

“Any infant will die if it doesn’t become part of something. […] it is precisely this dependence that allows it to acquire complex, culturally determined capabilities and behaviors. […] the absence of autonomy, could be a factor in the emergence of complexity.”

Complex behavior includes language and exchange of knowledge, as when the child mirrors their parents’ communication. Since language is one of the most complex skills developed from the absence of autonomy, Ameisen uses the disjunction between life and how we talk about it as a prime example:

“We say, “I am alive” despite the fact, that we would be more correct saying “we are alive” instead.”

Exchanging temporalities

The interdependency of social stimuli and the vital necessity to be part of something and in relation to someone, also makes me question the new perception of time as something we are almost outside; from contemporary to extemporary. Toke Lykkeberg says that extemporary art cannot be reduced to a single generation, “because what they (the artists across generations, red.) share is the very feeling of no longer working and living within a clearly defined period of time.”

In a review published in ATLAS, Nanna Friis observes Sif Itona Westerbergs ability to underline time as circles. “The time we live in, is all the time everything that has been before it, and thus all the time bigger. There will all the time be more of everything, which a new “we” all the time can use to create the next, but what we sense and feel elementary, seems to repeat. […] The world wishes to see itself, as Inger Christensen wrote”.

“At ARoS I overhear a group of young people, clearly students at the art school, I think to myself, possibly drunk or high, criticizing the exhibition rather loud and explicitly.”

At ARoS I overhear a group of young people, clearly students at the art school, I think to myself, possibly drunk or high, criticizing the exhibition rather loud and explicitly. I soon recognize an old friend among them, and it turns out, he’s their teacher at the Aarhus Kunstskole, preparing them to apply for fine art academy. With this article in mind, I ask them to share their critique with me, and it seems like what they are mostly unsatisfied with, is little details such as the screws holding the aluminum tubes together.

The construction of the works and the production of the show does not live up to their expectations of an ARoS exhibition. “It would be fine if it was a show in a small space somewhere, but here at ARoS they have so much money, so why don’t they use them on proper production?” one of them says.

Even though I must admit that they have a good reason to question where to all the money goes in this big machinery of the entertainment industry, I try to suggest that perhaps the top of the mountain is not necessarily as privileged a place as they imagine it to be. I hate to ruin their dreams of becoming rich and famous through art, but the truth that I know of, is simply that everyone struggles with budget and time constraints, no matter how big it gets. I realize that this is not what they need to hear, but I think what I actually wish to tell them is more about not being too harsh on one another.

“The world out there is a tough enough place as it is, you do not need to ruin it for each other along the way. Stick together and help your colleagues, instead of spending too much energy criticizing them as competitors.”

“The world out there is a tough enough place as it is, you do not need to ruin it for each other along the way. Stick together and help your colleagues, instead of spending too much energy criticizing them as competitors.”

I think I said something like that, and it seemed as if it resonated with them, because all of a sudden, they told me that they actually all agreed that it was a great show, they just expected more.

And I think this is the whole point; the next generation are bored with representations of what went wrong, when, where and why. They ask for more than a theatre act, they are ready to act and expect older colleagues to do the same. They will not let themselves be satisfied with anything less, art being no exception, of course, since for this group of young people, I imagine that art is what their lives are all about and their passion gave me energy for the rest of the night, even though I must admit, I felt a bit old.

Photo: Malou Solfjeld.

Photo: Malou Solfjeld.

Awkwardly, I told my friend that I’m pregnant, and all of his students started clapping and cheering and congratulating me, and in retrospect I wonder if I said it out of panic, as if I was trying to convince them (and myself) that there are other things than a successful career in the arts, worth living for…? As if standing there giving advice made me realize that those days of getting drunk at openings and demanding more from the sunset (and the rainbow), no longer belonged to me as much as to them.

We may be circling in time, as Nanna Friis suggests in the sense of Inger Christensen’s Möbius strip; “I think, therefore I am part of the labyrinth.” Meanwhile, we are all extemporary; out of time and with neither progress nor regress in horizon… The implosion of time, I believe, can easily lead to existential loneliness if we do not experience any defined time to belong to. Our social relations may transcend the urge for belonging to a time once we realize that there are a multitude of times, timescapes and timescales, open for us to relate to and become part of; one of them being Sphagnum Time.

ARoS Museum (Olafur Eliasson, Your Rainbow Panorama). Photo: Anders Trærup.

Fermenting Data: Sphagnum Time

Immemorial was on view during the autumn of 2021 at ARoS, the iconic flagship museum dominated by Olafur Eliasson’s Your Rainbow Panorama, shedding new light on the entire city since 2011. The rainbow is a transition itself, a portal between rain and sun, here and there. Where it ends, the grass must be greener. But what most promises like this, rarely reports, is that the treasure comes with a price. The grass may be greener, but nobody cares to ask why. If we did, we would perhaps find out, that the soil with the greenest grass has been fertilized in a certain way. Artificially, chemically or organically. One way or the other, the end of the rainbow is not an illusion, as I see it, but the question is how much we are willing to pay, to get there.

“The grass may be greener, but nobody cares to ask why. If we did, we would perhaps find out, that the soil with the greenest grass has been fertilized in a certain way. ”

In a differently located and independently run project space in Aarhus, Spanien19C, the Danish expat artist Sissel Marie Tonn (currently based between The Netherlands and the UK), exhibits data borrowed from a Dutch museum hosting the remains of our ancestors.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

During a residency in Aarhus earlier in 2021 she collected data as well from the local Moesgaard Museum, famous for their conservation of the oldest bog body found in Denmark, Grauballemanden dating more than 2000 years back in time. Through moss, microbes, minerals, molecules, isotopes, pollen, fungi and water, Sissel traces possible tales, explaining the transformation of life in the bog; from decayed human to other states of being.

The work Sphagnum Time consists of photogrammetric readings (3D renderings made from photographs) of three bog bodies. Combining artistic and scientific methods, the bodies are turned into data, and given voices by the artist to tell a speculative narrative of their lives in the bog, and how the conditions of the dried-out wetland have changed within their time.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (still).

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (still).

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (still).

It is fascinating to sit in complete darkness and listen to the conversation between the three bog bodies displayed on three different screens: “I remember becoming something else, the blood leaving my body seeping into the bug, the lifeforms inside me dying out, the moss growing around me, cradling my body – new kinds of organisms making me part of this environment.” Thus speaks one of them, before the next one describes the sensorial experience of living in a bog: “The water has a metallic taste, slippery, sleak, shiny, penetrating my skin. It feels ichy, and it’s making me restless.” The reason for these uncomfortable changes in their environment, a third bog body explains: “Some humans above ground were using chemicals to impregnate wood. It extends time and resists the logic of decay.” “It mutates inside me” answers the second one, before they all agree: “The environment passes through us in waves, leaving behind its traces.”

The exhibition is installed in the temporary space of Spanien19C; a container located close to the harbor in a part of the city currently undergoing unprecedented changes of redevelopment. Like the Fermenting Data partner-exhibition at Andromeda8220, located in the outskirts of Aarhus, the content of Sphagnum Time anticipates a transition zone, reflecting its surrounding environment. In the 3-channel video work on display inside the container, we learn that for thousands of years, the bog was perceived as the portal between living humans and their ancestors, gods, and demons.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (2021). Foto fra værkets installation i Sydhavnen, Aarhus. I samarbejde med Spanien19C. Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

A contemporary portal made in 2021, in collaboration between the artists, the curators and their shared research is gathered here.

Anders Visti, Andromeda and the gentrification of Gellerup

With Fermenting Data, the curators Magdalena Tyżlik-Carver and Anders Visti aim to consider data as a generative practice.

Rather than based on extraction, exploitation, and surveillance, as one may say is the case for most data collecting methods in urban planning; they re-imagine data as a positive force. Taking inspiration from fermentation and symbiosis, they ask how these naturally occurring phenomena can inspire constructive and equitable data practices.

At Andromeda 8220 the sound work of Anders Visti is presented, in which he uses data such as conversations, sound recordings and photographs from Gellerup, mixed up with publicly available data and data collected from social media platforms. The artist thus uses machine learning technologies to register and perform with data how the area with its current inhabitants are affected by the major urban reconstruction work.

Anders Visti, AaUOS, Aarhus Urban Operating System (2021). Performance. Gellerup Art Factory. Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Anders Visti, AaUOS, Aarhus Urban Operating System (2021). Video still, detail. 3D-model: Jesper Carlsen.

Anders Visti, AaUOS, Aarhus Urban Operating System (2021). Screenshot, detail. Recurrent Neural Network, trained on the development plans for Gellerup and Toveshøj.

Opposite the immaterial nature of his performative work, the development of Gellerup focuses on the physical restructuring of the neighborhood. The latter is supported by data from a series of similar regeneration projects in other European cities. Supposedly providing evidence that the demolition of housing in certain city districts – and its subsequent social effects – are desirable because they reclaim these areas as “safe” for residents of the city. A violent performance carried out on entire neighborhoods.

Whereas Anders Visti ferments data into an immaterial sonic sphere, Magda combines an aural dissemination of her curatorial thoughts with a walk. She accompanied me on an Echoes tour around Gellerup, beginning at Andromeda8220. It is intense to move around the area that is doomed to demolition due to its politically termed status as a “ghetto”. I witness the gardens and streets of people who are being kicked out of their homes in explicit protest: homemade banners hanging from their windows saying, “Protect our public housing” or “Cancel the ghetto law”.

“I witness the gardens and streets of people who are being kicked out of their homes in explicit protest: homemade banners hanging from their windows saying, “Protect our public housing” or “Cancel the ghetto law.”

Build between 1968 and 1972 as a counteroffer to the city center’s poor housing opportunities, Gellerup was inspired by Le Corbusier and his modernistic, functionalistic ideas of creating better conditions for living in the city. In the meantime, a new social experiment is carried out by the Danish government, which has so far led to the demolition of twelve buildings (apartment blocks, schools etc.) since 2013.

The re-location of people is brutal in and of itself but considering the 80 different nationalities representing the inhabitants of Gellerup, I cannot help but imagining that this is not the first time many of them have been forced to leave the place they call home, and I wonder what sort of alienation, insecurities, feelings of detachment and re-evoked traumas will come along in the process of gentrifying this neighborhood…

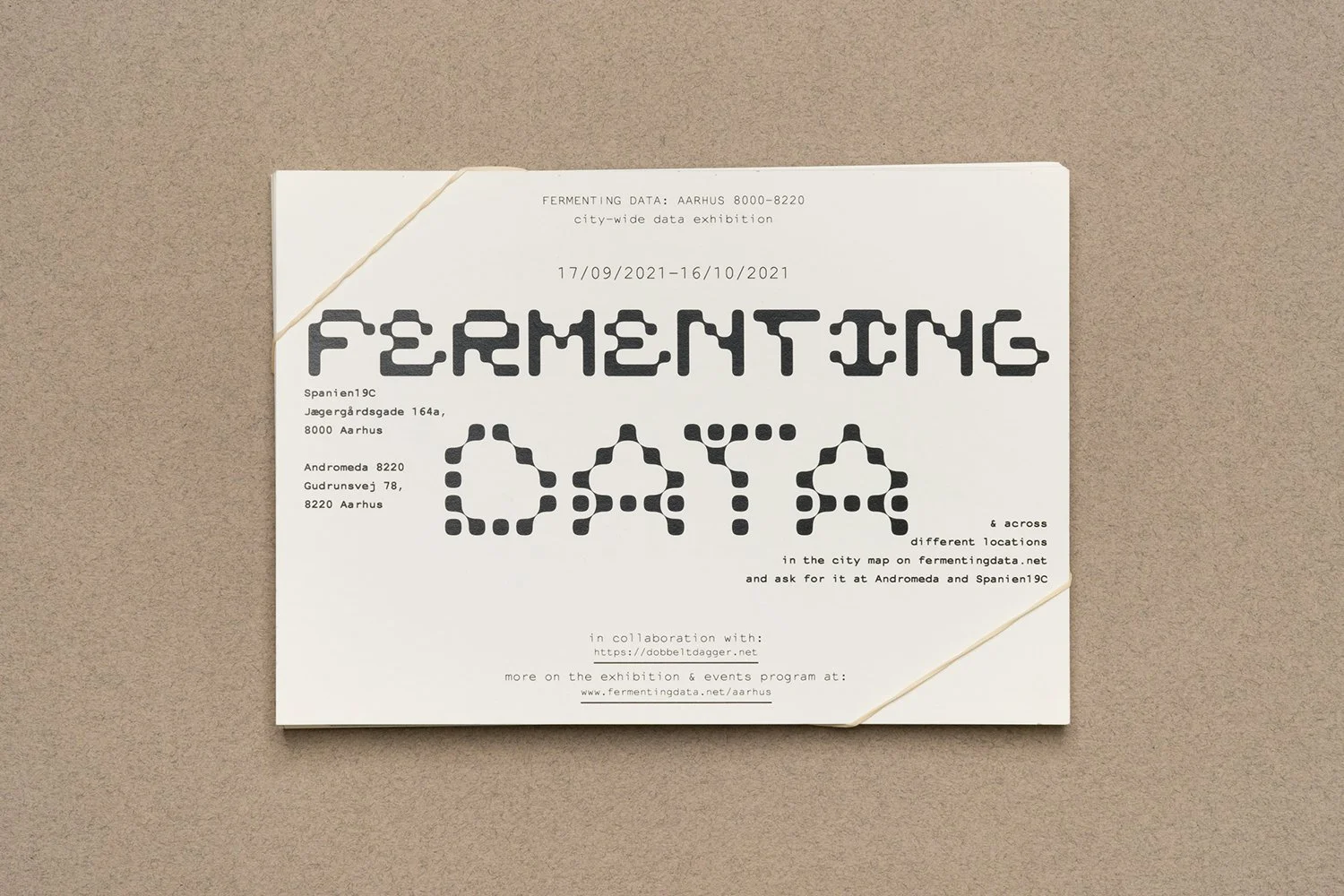

Publication from the exhibition Fermenting Data. Graphic design: Joana Chicau. Photo: Luna Lund Jensen.

Publication from the exhibition Fermenting Data. Graphic design: Joana Chicau. Photo: Luna Lund Jensen.

Publication from the exhibition Fermenting Data. Graphic design: Joana Chicau. Photo: Luna Lund Jensen.

Publication from the exhibition Fermenting Data. Graphic design: Joana Chicau. Photo: Luna Lund Jensen.

Publication from the exhibition Fermenting Data. Graphic design: Joana Chicau. Photo: Luna Lund Jensen.

Contamination of the environment

I honestly cannot avoid considering the people behind the Ghetto law as speculative, capitalist, mean and invasive species contaminating all these people’s homes with a feeling of having no rights to stay, no right to be as they are. Arriving with their demolition equipment as if they were there to poison weed, not paying attention to the actual families and communities, whose lives they are stirring up and tearing apart. These toxic so-called “regeneration projects” makes me want to return to the rainbow and the greener grass metaphor, and to “roundup” (pun intended) I would like to draw attention to a former work by Sissel Marie Tonn; Water thieves and time-givers. The audio work researching the infamous Teflon producing company DuPont, and their PFOA leakages in the ground water can be accessed here.

I can also recommend the movie Dark Waters on Netflix, which adds the Hollywood horror to this true crime disaster, treated by Sissel in her rather poetic and personal work. In general, Sissel is worth following, if you are curious about the entanglement between humans and other species; examined through manmade natural disasters such as earthquakes caused by intense gas drilling and microplastic in the sea as well as in our own bodily waters. At the online exhibition Toxicitysreach, you can watch her Plastic Hypersea (the spill), in which she invites the beholder to “imagine the environment as an extension of their immune system.”

Fermenting Data RAM (2021). Andromeda8220, Gellerup. Installation med indhold fra projektets workshops i Andromeda8220 og fra Den Grænseløse Festival, Ebeltoft. Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Fermenting Data RAM (2021). Andromeda8220, Gellerup. Installation med indhold fra projektets workshops i Andromeda8220 og fra Den Grænseløse Festival, Ebeltoft. Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

Fermenting Data RAM (2021). Andromeda8220, Gellerup. Installation, detalje. Fermenteringer og udstillingspublikation. Photo: Mikkel Høgh Kaldal.

We are alive

Whereas Fermenting Data and Sissel’s overall praxis centers around political, chemical and most importantly ecological changes in the body and its environment, Sif Itona Westerberg reflects on the connections between mythical hybrid creatures and contemporary gene modified cross-species, combined of wo/men and other fabulous animals in the laboratory through Crispr technology and different tools of mutation.

“As I am writing this – several months after visiting Aarhus (time truly changes when your body hosts no longer only one, but two different heartbeats at the same time) – I am currently infected with the new covid variation Omicron.”

As I am writing this – several months after visiting Aarhus (time truly changes when your body hosts no longer only one, but two different heartbeats at the same time) – I am currently infected with the new covid variation Omicron. I realize that my baby is not anymore merely conceived from the two cells that used to belong to his father and myself, but also shaped by a certain microorganism, which seems to have travelled all the way from a Chinese bat across the globe to arrive in Europe, in Denmark.

From these days on, Mio – which is the name of our baby – has been host to the infamous virus named Covid19, and can therefore in my perspective be categorized as a crossover between woman (me), man (his father), bat and germ. At least. Cause we do not know yet how many other animals have hosted the virus and left their mark on it before it came to us.

It is fascinating to realize that now I am no longer the only one hosting a guest inside of me, but my partner and my baby are in fact as well carrying something alien. One may argue that neither the virus nor the vaccine is alive – but this is somehow debatable.

“Viruses are inert packages of DNA or RNA that cannot replicate without a host cell. A coronavirus, for example, is a nanoscale sphere made up of genes wrapped in a fatty coat and bedecked in spike proteins.” (from Sciencenews.org)

So, it may not be alive at the time of entering our bodies, but once the spikes have attached themselves to our cells, it becomes part of our living, our being, and what’s to me most interesting of all, the virus is now a part of Mio’s process of becoming human. Even though it may only be a tiny fraction, that is made from this non-human species, it is still there, growing along.

Luckily, we have all three overcome the worst part of feeling sick from the intruder, but which long term impact it has left on us, is still a question that needs to be answered. We do not know if it will ever fully leave us again. Conclusion: When I give birth in a few weeks, it will not only be a human baby, but a human baby with a tiny fraction of bat inside the DNA…

“I hope this gives Mio extraordinary skills of echolocation, to communicate with animals under the water as well. To connect with our wet ancestors and to survive in a future of rising sea levels.”

I hope this gives Mio extraordinary skills of echolocation, to communicate with animals under the water as well. To connect with our wet ancestors and to survive in a future of rising sea levels.

”The most useful guide to the country we’re visiting”

So what did I learn from the data driven destruction of Gellerup mixed up with Sissel’s research on contamination and Sif’s Crispr inspired mutations? I believe it all leads me back to where I started putting my curatorial research focus quite some years ago; the question of home, its meaning and matter.

During the first lockdown in 2020 I hosted a podcast called Reading continues at home – it was a digital extension of the reading group I had initiated in Vienna just before the pandemic took over. The first episode was called The body as our home; the planet as a common body and a shared home. I guess the journey to find home – which started for me in 2019 as a two months interrail journey from Mallorca where I lived to Copenhagen where I was moving back to – intensified as an introspective and bodily journey during Covid. Isolated and constantly reminded about the fresh air, the toxic air, the breath that may kill you or keep you alive was a huge stress factor but also indeed a steep learning curve in many ways.

I am very lucky that I have never experienced what the people in Gellerup are going through, but grieving over something we haven’t lost yet, and living with the fact that our home is in decline, that the planet as we know it is undergoing radical decay, is something I spend a lot of time worrying about; and in fact there is a word for this: Solastalgia it is called (Recently Madeleine Kate McGowan created an incredible 48hour performance using Solastalgia as its title and theme; a so-called sci-fi musical).

Feeling homeless in my own body is also something I’ve known all too well for way too long. Now it is no longer only a matter of making myself feel at home since I have all of a sudden become a home to someone else. This automatically forced me to treat my body as a home, to nurture it and make peace with it, accept its traumas and response signals and finally learn again how to trust it, inhabit it and collaborate with it instead of trying to tame it, ignore it or suppress it. I am awkwardly aware that ghetto laws and gentrification are far away from my little privileged preggo corner of the world, but what I wish to encourage is an expanded awareness of what makes people feel at home; even in times of transformation whether that may be through a pig heart surgery, a pandemic, a rehousing, a pregnancy, an education or an exhibition. All these transformative states will in each of their way have that one thing in common, which is the question of home.

“Now it is no longer only a matter of making myself feel at home since I have all of a sudden become a home to someone else.”

If we treat our bodies as home, safe but open at the same time, I imagine that we will all benefit from these shared communities that our bodies’ extended environment constitute with one another; constantly exchanging energies, bacteria and sometimes even words or other forms of language, with the ones we surround ourselves with. I’ll finish off with the words of Ursula K. Le Guin which keeps moving me every time I read them:

Home isn’t Mom and Dad and Sis and Bud. Home isn’t where they have to let you in. It’s not a place at all. Home is imaginary.

Home, imagined, comes to be. It is real, earlier than any other place, but you can’t get to it unless your people show you how to imagine it – whoever your people are. They may not be your relatives. They may never have spoken your language. They may have been dead for a thousand years. They may be nothing but words printed on paper, ghosts of voices, shadows of minds. But they can guide you home. They are your human community.

All of us have to learn how to invent our lives, make them up, imagine them. We need to be taught these skills; we need guides to show us how. Without them, our lives get made up for us by other people….

–

Nobody can do anything very much, really, alone. What a child needs, what we all need, is to find some other people who have imagined life along lines that make sense to us and allow some freedom, and listen to them. Not hear passively, but listen. Listening is an act of community, which takes space, time, and silence. Reading is a means of listening. Reading is not as passive as hearing or viewing. It’s an act: you do it. You read at your pace, your own speed, not the ceaseless, incoherent, gabbling, shouting rush of the media. You take what you can and want to take in, not what they shove at you fast and hard and loud in order to overwhelm and control you. Reading a story, you may be told something, but you’re not being sold anything. And though you’re usually alone when you read, you are in communion with another mind. You aren’t being brainwashed or co-opted or used; you’ve joined in an act of the imagination. Books may not be “books,” of course, they may not be ink on wood pulp but a flicker of electronics … The technology is not what matters. Words are what matter. The sharing of words. The activation of imagination through the reading of words. The reason literacy is important is that literature is the operating instructions. The best manual we have. The most useful guide to the country we’re visiting, life.

Cover photo: Sissel Marie Tonn, Sphagnum Time (still).

Malou Solfjeld is an art historian and curator working with notions of be-coming, co-habiting, collectivity, care, ecology and environment – bodily, mentally and geopolitically. She has contributed to idoart.dk since 2020 with essays, reviews, and travel journals. In 2022 she is becoming a mother and will continue to reflect on what it means to find home, come home, be at home or become a home, on Planet Earth, and how to feel at home within oneself, in times dominated by several entangled crises.