HANNE LISE THOMSEN: PHOTOGRAPHY BEYOND FOUR WALLS

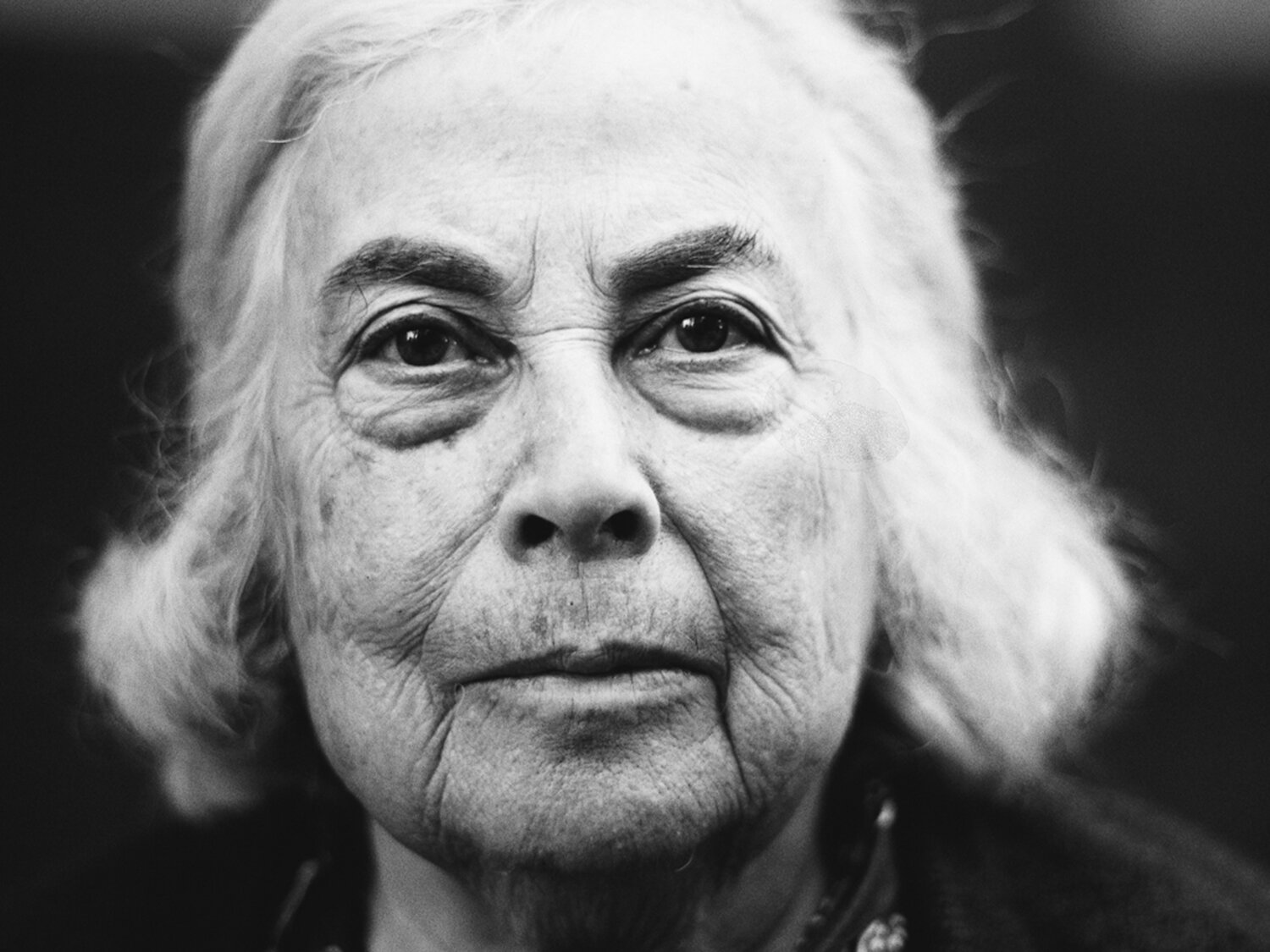

The Danish photographer Hanne Lise Thomsen (b. 1951) is an example of an artist whose practice is marked by community involvement and everyday life. In her latest book, Hanne Lise Thomsen (a survey of her projects from 2002-2016) you see a photographic work in which the commonplace is woven with the everyday. The black and white or color photographs of anonymous people draw a new image of the city and its history – important testimonials that can help us understand the problems we still face today.

As a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, she mainly interviewed over one hundred women artists over 40 years of age, many of them from the Kvindelig Kunstnersamfund (Society of Female Artists) as part of a collaborative student project co-organised with her student colleague, artist Else Kallesøe. This was shown in the landmark exhibition Kvindeudstillingen XX (the women’s exhibition XX) at Charlottenborg in 1975.

This unprecedented exhibition featured 70 artists, including national artists like Lene Adler Petersen, Susanne Ussing, and Kirsten Justesen; and also many international artists such as Marina Abramovic, Carolee Schneeman and others. In Denmark, this exhibition is considered the first meeting place where one could encounter other foreign women artists. Nevertheless, this major exhibition event has not completely earned its place in Danish art history. The drive of such an international collaborative artistic activity, between coordination and creation, was not only the first, but also seeded the model for Thomsen’s future practice. Where in her works, she approaches communities and develops a visual narrative out of their ordinary life.

Else Kallesoe and Hanne Lise Thomsen doing their research project for Kvindeudstillingen XX in 1975 (here seen interviewing the artist Kamma Salto). Photo courtesy of Sonja Iskov.

Thomsen is one of those pioneering artists like Jytte Rex or Ursula Reuter Christiansen for whom the experience of the women’s movement and art, shaped how they would approach women’s rights and artistic independence.

As a viewer-reader of her book, you are enticed by her sensorial universe. From New York to Copenhagen, and via Marrakech, the separation barrier of the city seems to be torn apart. Oppressed or marginalized populations, such as women or the homeless, are embraced in the socio-political debate of our societies. Anonymous people appropriate urban art by becoming actors in her productions, where the biggest photo exhibition of all takes place outside the four walls. Hanne Lise Thomsen achieves this tour de force in direct collaboration with local populations, and by seeking the recognition of the Other. And because this form of urban intervention stands in opposition, it highlights what the world’s gaze is not usually directed at.

Why photography? Photography has the capacity, because of the creative investment that it requires and the process of image projection that it causes, to form identities, to interrogate them and to transform them.

Photography thus creates a space for dialogue and activism that can be used to try to weave and solidify the links between divided individuals from the same society that go beyond preconceived ideas. This is particularly the case with Thomsen’s project Inside Out Shuafat, in East Jerusalem in 2011. This work has a participative approach that consists in providing children with cameras, in this case, to capture images of their reality, in order to produce personal photographs capable of deconstructing stereotypes.

Inside Out Shuafat Refugee Camp, East Jerusalem, 2011. Photography by Dana, Diala, Mlak, Sandra and Nadeem (kids from Shuafat Refugee Camp).

Inside Out Shuafat Refugee Camp, East Jerusalem, 2011.

Photography by Dana, Diala, Mlak, Sandra and Nadeem (kids from Shuafat Refugee Camp).

Inside Out Shuafat Refugee Camp, East Jerusalem, 2011.

Photography by Dana, Diala, Mlak, Sandra and Nadeem (kids from Shuafat Refugee Camp).

In Hanne Lise Thomsen, Jeanne Betak (book designer), wanted to open these perspectives, which are reinforced by the English and Danish texts by art historian Ditte Vilstrup Holm and historian of photography Mette Sandbye.

Born out of a unique North African-Scandinavian collaboration, the project Billboard Festival in Casablanca in 2015 builds bridges between cultures and questions our ideas for urban space, gender, and identity. The festival supports a new genre that represents women, via artistic interventions and images mainly produced by women. Where the billboard format, which is a powerful vector of visibility in public space, allows contemporary art to confront a wider audience – composed of thousands of city dwellers, motorists, pedestrians – of any age and gender. Against this background, Hanne Lise Thomsen's goal is to broaden the talent and vision of stories and images that break with the commercial ad space that dominates the streets of the world's major cities, and in the process of her installations, help raise awareness and open up public debate about gender issues. Where initiatives like the Billboard Festival give women the opportunity to express themselves in their own words and to make the city a source of creative inspiration for everyone. For these street projects, she invites other photographers or artists to make the images. In this sense, she curates or directs the project.

Work: Hind Bensari (MA) Burqanista, Billboard Casablanca Festival 2015 / Location photography in Casablanca by Hanne Lise Thomsen.

The poster is a means of expression that developed during the nineteenth century with the industrial revolution and urban development. Even today the poster is everywhere, an heir to these evolutions of the past, and at the same time conserving its graphic, photographic, or digital creation.

However, the billboard remains a testimony of a time, of the evolution of civilization, a mirror of the history of viewing things in public. And as such, Thomsen's projects aim to empower forgotten populations through this form of street art by encouraging the representation of strong figures. Feminism in the streets of Casablanca highlights the way in which visual rhetoric constructs the problem of women's place as a social problem while describing general trends and ideologies that have developed over time.

Work: Nike Åkerberg (‘Å’) Untitled Billboard Casablanca Festival 2015 / Location photography in Casablanca by Coline Marotta.

Projection: Inside Out Istedgade, Copenhagen, 2009 / Location photography in Copenhagen by Anders Sune Berg.

Even today, urban or street art seems to be an additional obstacle for women. Gender makes a huge difference when you move into the field of street art, where women artists feel vulnerable. A discomfort in public spaces is a feeling that many women can understand. In this sense, Hanne Lise Thomsen, through the eyes with which she photographs and projects onto surfaces, brings to the city emotional as well as visual experiences: where walls speak, leaving behind traces of women, who sometimes speak. With these public representations, Thomsen provokes meeting points or spaces where freedom, sharing and questions rhyme with public forms of humanism; and with these forms she seems to want to give a soul to the walls of cities.

The Homeless of New York City Wish You All a Happy Holiday, December 2005. Research photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen / Location photography in New York by Jean Christian Bourcart.

Such art practices are actively involved in an alternative city-making process, one which is open, interactive and collaborative. In addition to encouraging the values of sharing, gracefulness and dialogue between generations or social classes, but also change that the practice conveys and which stimulates citizen involvement. Her project The Homeless of New York City Wish You All Happy Holiday illustrates it very well. 40 black-and-white portraits of homeless people were projected onto a wall at the corner of Broadway and Howard Street. With this projected text, Thomsen lays bare how Manhattan is a symbol of Western wealth and consumerism. Here, the project highlights the almost absurd social inequality by drawing attention to all homeless people in this city – giving them a public voice and a face.

The Homeless of New York City Wish You All a Happy Holiday, December 2005.

Research photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen / Location photography in New York.

The Homeless of New York City Wish You All a Happy Holiday, December 2005.

Research photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen / Location photography in New York.

This urban interventionism is a reflection on the urban space, its plasticities, its representations and the artistic acts it shelters, conditions or incites. The artist discovers a space of fascination, a field of displacement and projection. Each pedestrian crosses the spaces of the city to surrender to time, because the city is itself a monument made up of many layers that solicit its memory and activates it. Hanne Lise Thomsen’s artistic expression opens a place to inhabitants in the city, but also discovers a territory outside of its inhabitants. The work is surprising in its size, location and push for dialogue.

Thomsen, with each production, attempts to make her art a unifying and democratic act. The goal is not to embellish but rather to integrate the work in a context and peg it to the lives of urban dwellers.

For example, in 2015, Hanne Lise Thomsen developed a work involving 40 apartments whose photographic and sound narratives contributed to multiple interpretations of the neighborhood of Vesterbro. She is particularly fond of Vesterbro, Copenhagen's historic and now gentrified western district. The area was known for many years to be the center of prostitution and drug trafficking, especially on Istedgade. Vesterbro has undergone an urban renovation policy for over a decade now, which has brought to its neighborhood the Metro service. Here, Thomsen’s projected images toiled with the transitions and emotional life of the people who live near Istedgade.

Inside out Istedgade, Copenhagen, 2015. Location photography by Torben Eskerod.

For Hanne Lise Thomsen, there is a need to develop an interdisciplinary look at works of art in public spaces, in order to better understand their possible contributions to the social life and urban culture of the cities she engages with her work. In this respect, audiences – which will be defined provisionally as individuals who come into contact with these projected photographs – are the first part of the social dynamics of the public space she quantifies with her work. Artists like Thomsen have chosen to work in collaboration with communities to make their works more inclusive and representative. These creative processes were named "new genre public art" or "public practice" by Suzanne Lacy (1995/06), or "art in the public interest" by Arlene Raven (1989). Recalling Walter Benjamin's figure of the flâneur, these artists linger on the peculiarity of the experience of their works by approaching the covert nature of this experience – which is most often anonymous in the city – in order to better underwrite the "real" in their productions.

Inside Out 2400, Copenhagen, 2012. Research Photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen.

Inside Out 2400, Copenhagen, 2012. Research Photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen.

However, is urban art still relevant today?

Born in the illegality of which its most brutal form of street-art was practiced, today urban art is no longer underground. Taken up by the institutions, festivals or the art market, the evolution of urban street art or public art projects generates new situations, which are interesting to study, also from the point of view of aesthetics (i.e. widening the collective body of work of this art form in the public sphere); sociology (i.e. the recognition of the value of works by citizens); politics (i.e. the valorization of emergence or the channeling of radical forces); or for cultural management (i.e. regarding the use of the city for marketing purposes). More broadly, the context is that of the creative city and urban imaginaries in this era of late capitalism, particularly in the place of a tension between the neoliberal or entrepreneurial approach to culture. From the point of view of the creators, how to combine a desire to challenge the system with the desire for recognition by the public and institutions, at the risk of being associated with missions of the socio-economic type (boosting neighborhood life) or destination culture (increasing the attractiveness of the city).

But the role of the artist remains, of course.

The research and debates imposed by Hanne Lise Thomsen makes it possible to rethink the contours of urban art in the face of its many detours. Festivals, although one might consider them among the entities responsible for the end of urban art, can also play an important role while offering themselves as opportunities for reflection and experimentation.

Passage, Copenhagen 2015. Installation view, images from private photo albums of refugees. Location photography by Torben Eskerod.

This is because, as soon as art is implemented in a public space, it confronts two polarizing options: to contribute to the enrichment of an ‘open-air gallery’ best defending the ideology of power in place (and generally sponsor of the work), or to adopt a critical position related to the context in which it is created to contest this ideology. It is then called ‘critical public art’, which will be spoken of in terms of some of its most prominent representatives since the 1960s: Gordon Matta-Clark, Krysztof Wodiczko, or Jochen Gerz.

All three artists were keen to propose a renewal of practices and topics by investing in the public space as a citizen forum, where people were invited to participate in urban performances, built on the challenge of a system that broke with expectations or the hopes of city dwellers.

These types of approaches suggest that, fortunately, although urban art seems to have somewhat achieved its function previously linked to a radical autonomy, a real independence, or a vocation to create shock (despite being today a totally different thing) these approaches can still be capable of modifying and questioning the real. In order to transfigure it, to build new identities, to express something really important, such as the participation of unseen and invisible women, the working population or the marginalized homeless. In Hanne Lise Thomsen’s project, Working Class Heroes in Damascus in 2011 (one of the oldest cities in the world, and today destroyed) the faces of street vendors replaced the president Assad’s own posters that line all the facades. This work offers something to the city, to make the Syrian people known. Each in their individuality composes the diversity of this city. As such, the project was stopped by the secret police.

Portrait of the street vendor. Working Class Heroes, Damascus, 2010. Photography by Hanne Lise Thomsen.

Unlike works exhibited in museums, galleries or art centers, Hanne Lise Thomsen’s works, which are integrated into public spaces, have public sociability as the context of presentation.

Unquestionably, her works are not static objects. In this regard, the American sociologist and urban planner William H. Whyte (The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces) does not hesitate to say: "It is a very sociable element".

Hanne Lise Thomsen by Hanne Lise Thomsen is published by Really Simple Syndication Press and is available online from the RSS Press Shop (275 DKK).

The book is on sale at SixtyEight Art Institutes December Bookshop which closes this Saturday December 21, 2019 at 6 pm. More info here.

This title is also available at SixtyEight Art Institute, Arnold Busck Købmagergade, Charlottenborg Kunsthal, and Malmø Konsthall.

Hanne Lise Thomsen by Hanne Lise Thomsen, published by Really Simple Syndication Press.

This essay and review is part of an initiative to foster Danish and English language critical writings from a range of new talents across the visual arts; and as a partnership between I DO ART and SixtyEight Art Institute.

This essay was translated from the French original by Hugo Hopping.

Severine Grosjean holds a Master of Humanities and Social Sciences, School of Advanced Studies in Latin America, University Paris-Sorbonne, Paris (France) and is the founder of The Nomad Creative Projects. She is currently an EU Erasmus Entrepreneur researcher at SixtyEight Art Institute. Severine has contributed to idoart.dk since 2019.