WORKING WITH CLIMATE CHANGE AS A WAY OF SELF-CARE

At Gothersgade 167 in central Copenhagen, a canvas covered with a thick layer of fungi and microorganisms is hanging in the window. The canvas seems to capture a winter landscape that is covered by caked earth and a hint of green life. It belongs to the work Naturografia by Italian artist Roberto Ghezzi, which is part of a group exhibition titled The Writing of Nature that features artworks by Italian artist Roberto Ghezzi, Swedish artist Åsa Sonjasdotter, and includes a scientific model created by scientists at Aarhus University and the University of Copenhagen. The exhibition is curated by Inanna Riccardi, and currently on view at the SixtyEight Art Institute until March 4, 2022.

The Writing of Nature takes as its point of departure the pressing climate crisis, and considers the concept of nature in contemporary society and the implicated relation humans introduce as the predominant source of the crisis. The exhibition inquires into what constitutes nature: is it a constellation of elements that also include humans? and how are these elements interconnected? All the while providing the ground for reflection on why climate change takes place and how it might be dealt with.

By juxtaposing artistic and scientific work, the exhibition also plays with the tension between science and art as two ways of conceptualising nature, and invites reflections on the effects of art and science in conveying our empirical experiences with nature.

The Writing of Nature (Installation view). SixtyEight Art Institute. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

As visitors enter the exhibition, they will find a continuation of the work in the window – two other canvases that seem to capture a similar “sighting”, hanging in contrast to each other. Beside these, there are watercolour sketches of the surrounding water, plantation, animals, and the situated landscape, which helps to elucidate the locales of the canvases. These belong to Ghezzi’s series of works called Naturografia, where he localises and materialises the processes of nature by installing organic cotton canvases in carefully chosen locations, such as, last December, in Fælledparken and Stejlepladsen in Copenhagen, or in a kolonihave (community garden) in Ballerup. Throughout the month, the local air, soil, fauna and flora left their traces through their interactions with the artificially placed canvases, manifesting the processes of nature into abstract artworks processed from the local winter landscape.

Beside the canvases and watercolours, QR codes are carefully placed which lead the visitors to texts that explain the ecological (such as vegetables and herbs); the institutional (such as property rights); and the social (such as historical makeup) environments of the locales where these canvas installations were embedded, reflecting the artist’s understanding of nature as a socioecological construct.

The Writing of Nature (Installation view). SixtyEight Art Institute. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

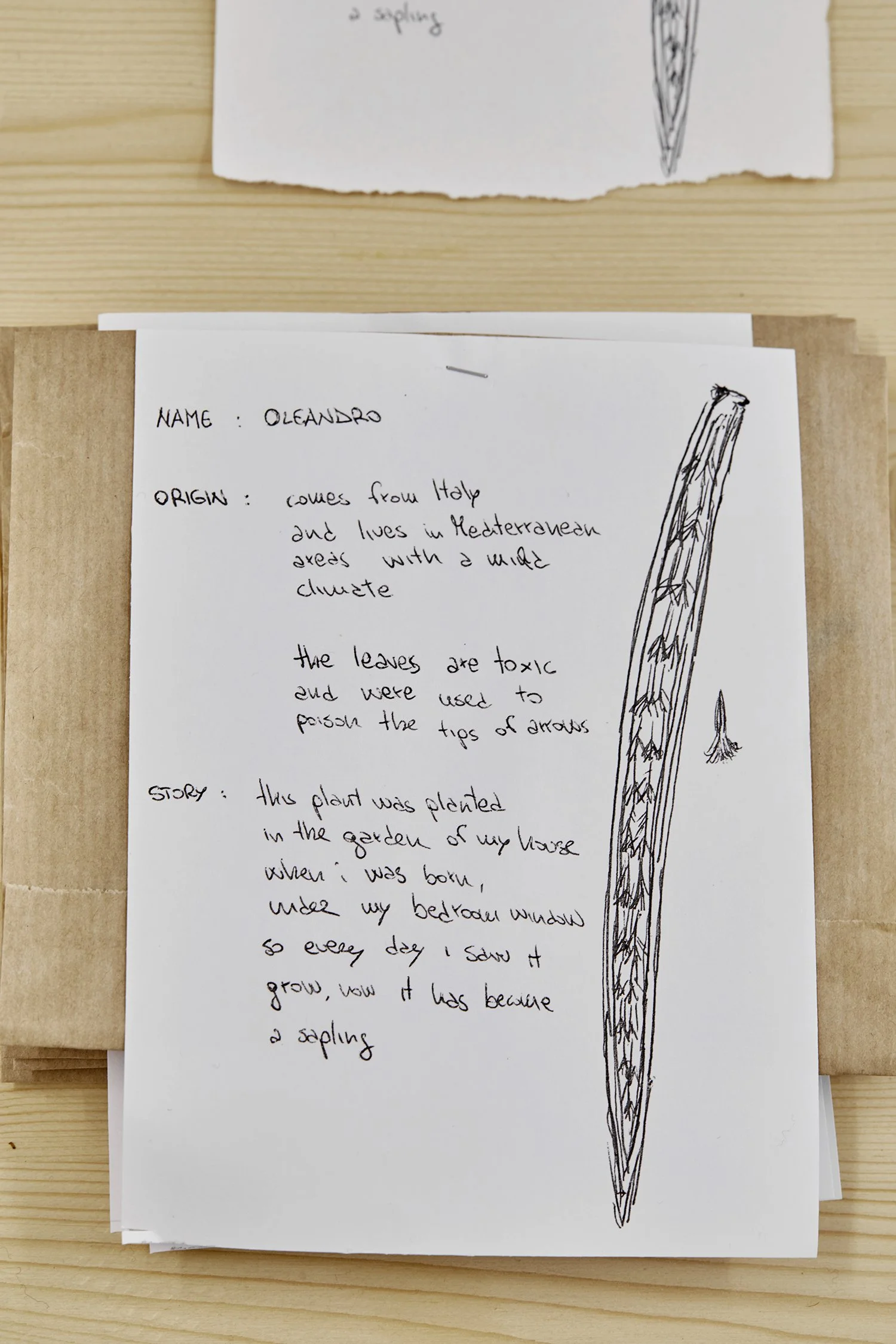

In the middle of the room, a dozen brown paper envelopes, each covered by a hand-written note, are lined up and displayed on a large, wooden table. Inside the envelope, the visitors can find the seeds of a particular plant. Each note on the envelope tells a local story about the plant. Some notes tell of how a wildflower, such as Zinnia, becomes a symbol and legacy of the grandparents’ love story in their garden, while other notes introduce the history of the use of Ruta herb in northern and central Italy. These packages are the result of the collective workshop, called Cultivating Abundance, which took place with the artist Åsa Sonjasdotter and 22 participants from Italy, Sweden, Denmark, Norway and the UK. In the workshop, Sonjasdotter guided the participants to use storytelling techniques to narrate stories of seeds that weave together personal, national and ecological life.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance (Results of workshop). Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Further into the exhibition, there is a study-like corner where visitors will encounter a different way of conceptualising, narrating, and experiencing nature. Here, visitors can sit down and interact with a digital map of air quality in Denmark on a tablet, checking the local concentration of nitrogen dioxide, PM2.5 and PM10 particles. A journal article is placed to the right of the device to illustrate how the digital map is made by providing a detailed account of how air quality is conceptualised, classified into categories, digitised, modelled, and coded. This illustration showcases another way of materialising air as an element of nature, and how the material experience of nature is inevitably a collaborative process between humans, artificial tools and the biophysicality of air that cannot be separated from each other.

The juxtaposition of scientific and artistic methods of conceptualising nature and representing these conceptualisations brings in an interesting tension between science and art, and their role in communicating the empirical experience of climate change locally.

The Writing of Nature (Installation view). SixtyEight Art Institute. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

In the curator Inanna Riccardi’s eyes, one of the hurdles in working with climate change is the abstract and difficult concept of nature. The goal of the exhibition is thus to create a space that can bridge the abstract concept and the empirical experiences of nature. But the exhibition is also political in the sense that Riccardi sees the exhibition as a counternarrative to the modern conception of nature as non-specifically human. Such a conception of nature believes rationality is a unique and essential force that defines the human psyche, separates humans from – and places them in superiority to – other species on the planet (1). This nonhuman other also includes the non-rational specifics of human persons, and whoever are deemed less human, such as racialised and gendered others. Such a conception of nature as non-specifically human lies in the foundation of industrial exploitation and extraction, which is a self-destructive process for humans and a primary cause of climate change. It also raises questions about who is worthy of rights, privileges, and protection in the face of the climate crisis.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

In The Writing of Nature, Riccardi draws on feminist theorist Donna Haraway’s concept of becoming with and the anthropologist Viveros De Castro’s notion of perspectivism, to invite visitors to reflect on our being as a first step to creating connections with the climate crisis.

The exhibition invites visitors to reflect on the relational dimensions of our being – “not as individuals disconnected from another but as beings who are interconnected and depend on each other for survival.” Riccardi further mentions that, “nature is us and we are nature.” This also means that knowing nature needs to be situated within, in Haraway's words, “a multitude of relations that also make possible the worlds we think with” (2).

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

These reflections are translated into the collaborative and local creation of the selected works in the exhibition. In these works, the constituents of a local ecosystem become protagonists or main characters in the creation of art, hence “the writing of nature”. For instance, in the creation of Naturografia, although the artwork is Ghezzi’s work in the sense that he chooses the canvas, the location and time of installation, and creates the medium by applying starch to each canvas, it is also about nature’s work in the sense that the water, soil, fauna and flora “draw” – through entropy and decomposition processes – the canvas. And the water, soil, fauna and flora take the centre stage of creation, carrying the same, if not more weight as the human creator. Each canvas is therefore a work of collaboration occurring between the artist and the ecological surroundings.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

This also means the knowledge about these co-created artworks needs to be situated in the local relations. Ghezzi’s work reflects a concern with the local, via a nomadic approach, in the sense that the canvas is installed wherever the artist is, telling the story of that place. In the exhibition, the canvas installation is displayed together with the watercolour sketches of the surrounding landscapes and animals, as well as a textual account of the historical make-up and property rights of the place, which as an artwork re-embeds the canvas in the various material relations of the land in focus.

Similarly, Sonjasdotter is interested in co-creating stories with seeds, and her work is primarily connected to the ecosystem, regulations, and people in Sweden. Nonetheless, in the workshop Cultivating Abundance, she asked all the participants to bring some seeds from their own country, which had a story. During the workshop the participants and Sonjasdotter worked on storytelling about the seeds which helped the participants to create connections with them, thus experiencing the seeds in a way that makes sense to their own being as well. Juxtaposing artistic works with scientific works, The Writing of Nature is also concerned with how we can capture and communicate our empirical experiences with nature. Through the exhibition, the curator Riccardi attempts to connect science and art, despite them often being seen as opposing approaches.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance (Results of workshop). Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance (Results of workshop). Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Åsa Sonjasdotter, Cultivating Abundance (Results of workshop). Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Riccardi sees the connections between science and art arise from a shared creativity, manifested as an urge to “think outside the box” and “look at reality from a different perspective than the established or conventional ways of understanding things.” Interestingly, in the exhibition, one could argue that both the scientific and artistic approaches are ways of creating empirical experiences with nature. While the scientists try to create ways of relating to air quality through the medium of modelling, the artists attempt to use canvas or storytelling as a medium to account for our experiences with soil and seeds. One may also see this contrast as a critique of the effectiveness of scientific expression of nature – intellectual reason, in communicating the climate crisis. Despite the involvement of human choices in the scientific construct of nature, nature is often explained through calculation and quantification (3), which do not always convey our embodied experience. Artistic expressions that reconnect us to nature through sensory experiences with painting and drawing, film and storytelling can thus complement the scientific expressions in communicating about nature.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

Roberto Ghezzi, Naturografia. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

In the end, does the exhibition serve its pedagogical purpose for educating the general public regarding the role of nature in our contemporary society? And can the approach of “becoming with” really shape our lifestyle?

I would like to answer these questions by bringing up one of my encounters at the exhibition: While I was viewing the exhibition, another visitor walked through the door and joined me. Before he left, the visitor told me he came back to take another look after seeing the exhibition at the opening in January. He grew up on a farm in Northern Jutland, where he had seen his parents using chemicals to reduce plant height in order to increase seed yield. He was surprised to learn that scientific studies have found that the higher the plant’s straw is allowed to grow, the more protein the seeds have. Seeing the exhibition made him reconsider his experience of farming in his childhood, and he would like to explore the topic more.

The Writing of Nature (Installation view). SixtyEight Art Institute. Photo: Jenny Sundby.

The world is struggling to find the solutions to the climate crisis since our individual agencies are largely mediated by social institutions through corporate, legal and industrial standards.

As with my fellow visitor, learning about our relations with nature through new reflections on nature is probably the first step. Working with climate change is a way of self-care: we have never been away from nature but simply blind to the full scope of our existence in nature. While the scientific methods and analysis help to reveal our becoming with nature, specially by indicating the impacts that we have on the world, the full scope of the issues we face can never be understood until they are localised through our emotional, cultural, and embodied experiences and reflections.

The Writing of Nature at SixtyEight Art Institute

on view till March 4, 2022.

Cooper, B., Smith, T. W., Hughes, G., Moschella, M., Geddert, J. S., Covington, J., ... & Beabout, G. R. (2016). Concepts of Nature: Ancient and Modern. Rowman & Littlefield.

Haraway, D., (1997), Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan _Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience, NY: Routledge.

Mennicken, A., & Espeland, W. N. (2019). What's new with numbers? Sociological approaches to the study of quantification. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 223-245.

This essay is part of an initiative to foster Danish and English language critical writings from a range of talents across the visual arts; and as a partnership between I DO ART and SixtyEight Art Institute.

Cancan Wang holds a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Fudan University, China, and a master’s degree in applied cultural analysis from University of Copenhagen, Denmark, through which she cultivated a broad range of intellectual interest in topics such as love, gender, technology and art. Pursuing her interest in art criticism comes from her work in information technologies and their impacts on social relationships, which she organized into a Phd in the field of information systems from Copenhagen Business School, Denmark. Cancan Wang works as an Assistant Professor at the IT University of Copenhagen and is based in Copenhagen.

Cancan has contributed to idoart.dk since 2019.