WE CAN STAY HERE WHILE WE WAIT: CLÉMENT VERGER

“My aim was to introduce more levels of information than what you could directly see in the photograph." - Clément Verger.

Clément Verger (b. 1988, FR) has studied visual arts and communication at the National Superior School of Arts, Olivier de Serres in Paris and was afterwards admitted for the Leonardo da Vinci European grant. He graduated with honours from a Master in Photographic Studies at the university of Westminster in 2011. His work questions the apparent wilderness of the landscapes that surround us. In his latest project Endeavour exhibited during We Can Stay Here While We Wait, Clément Verger isolates a specific example of the larger phenomenon that is the transportation and implantation of species across the world. The Eucalyptus tree and its introduction in Europe becomes a case study, a tool to analyse the complex patterns in man’s influence on its environment.

Clément Verger, The Historical Cultural Landscape of Portugal.

Clément Verger, Cabo de Roca, Colares in Portugal.

Clément Verger in conversation

E: What made you apply for the residency in Portugal?

C: Several friends sent me the application from The Independent AIR, people who knew my work, and it was an unusual amount, which really made me consider that I should have a look at it. The theme was the Anthropocene; a topic that has been central to my work since the last year of my Master, so the residency definitely picked my interest.

Another aspect of the residency that made me apply was the fact that it was a 6 months residency spread into two periods, and I was quite exited about the idea of working full time in Portugal on a personal project. I ended up working a lot on the project during the months in between and went to England at the end of the last period to work at Kew Gardens in the archives and the herbarium to finish the work.

Clément Verger, Eucalyptus forest.

E: How would your routine be when in Portugal?

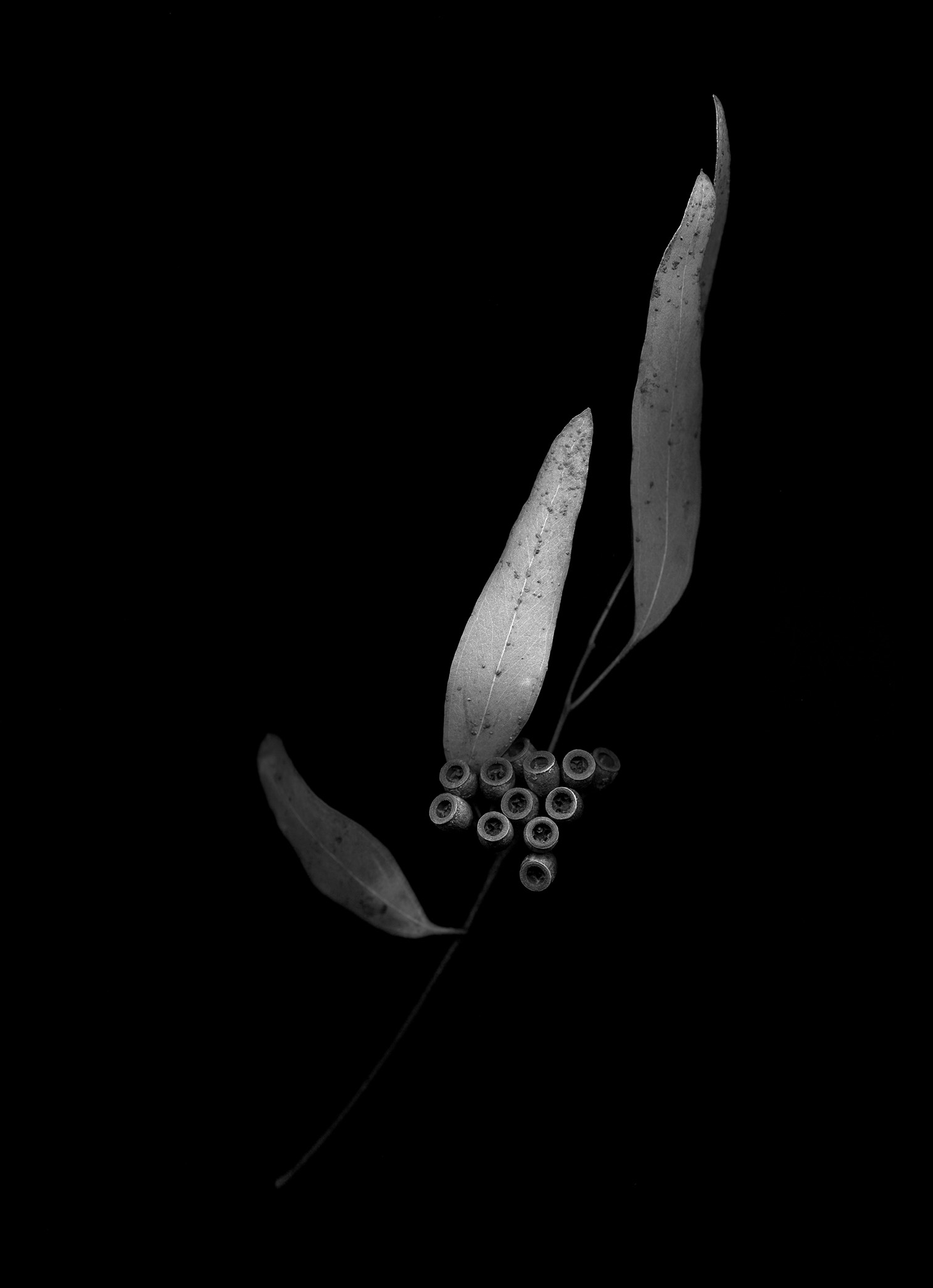

C: It was a mix of things. I was doing research most days, reading a lot of articles and the journals of Joseph Banks and James Cook, and also organizing the trips to locations around the country to photograph. I also try to simply walk around the eucalyptus forest near the house most days, and collect specimens of eucalyptus at different growth rate throughout the year, to create my 21st century herbarium. These images are made using a flatbed scanner as a camera which creates really detailed images and also conserve the actual scale of the plant itself.

Clément Verger, Collected samples of eucalyptus globulus.

One trip I went on was to Coimbra and its district to meet with the director of the botanical garden. The garden is the origin point of the introduction of the eucalyptus in the country and continental Europe. While there I went on a little expedition to find the oldest eucalyptus in Europe – trees that were planted in the area throughout the 1800s. There I found the tallest tree in Europe, a eucalyptus diversicolor called Karri Knight that was recently measured at 72m. Finding that tree was an interesting research exercise, crossing historical documents and discussions with the team at the botanical gardens, and, as there was no actual mapping of it, using the informations from pictures in articles to geotag on pictures from Google images to be able to finally find this giant tree tucked at the bottom of a valley.

Clément Verger, Coimbra district.

Clément Verger, Tallest tree in Europe, Karri Knight.

E: Your project is very geographically specific. Did you research before the residency or did the idea come to you while there?

C: I did a proposal for the residency with another concept, but when I arrived there in this house surrounded by a vast eucalyptus forest, I thought it was something to investigate. I knew the eucalyptus was endemic to Australia and I went on to research when, how, and why the eucalyptus was introduced in Europe. Pretty early on in the research process I stumbled upon the story of the Endeavour and the role of James Cook and Joseph Banks in it, and I realized that I had something interesting unfolding in front of me.

Clément Verger, Joseph Banks.

The work itself covers elements starting from what made the Endeavour expedition possible and why it was commissioned, and goes on to analyse the reasons eucalyptus was first brought to Europe. The final chapters of the project questions the modern development of the eucalyptus culture for the paper pulp industry and ends with consequences in terms of biodiversity, the forest fires and the diminution of the water reserve.

Clément Verger, Forest fire Monchique, Algavre, Portugal.

E: Is the consequences how the project relates to the Anthropocene?

C: Well, I tend to have a different definition of the Anthropocene than most people do. The common view of the Anthropocene is focused on modern changes often starting from the industrial revolution, and a lot of the thinking on that topic tends to have a really black and white vision. My research led me to see it as something more complex; as man has always intervened on its environment, it is just the means and the scale that have changed and created today’s imbalance. My position is more based on the idea of questioning the landscape that surrounds us and deconstruct it to reveal human history. I am more interested in people having the tools to question what’s around them and come up with their own conclusions.

So in the case of my project Endeavour, it was really about using the example of the eucalyptus to question a larger phenomenon that is the transportation and implantation of species across the world. The Eucalyptus tree and its introduction in Europe becomes a case study, a tool to analyse the complex patterns in man’s influence on its environment.

Clément Verger, Eucalyptus (eucalyptus globulus) blue gum.

Clément Verger, Eucalyptus (eucalyptus globulus) blue gum.

E: Do you usually approach your art as scientifically as this?

C: I have done so for some years now, and it has become a big part of my work process. My projects are researched based. I find it enriching to work and learn with people specialised in really specific fields. In a way starting a new project for me is like a journalist writing a story – you do have to become somewhat of an expert in a topic that might be completely foreign to you. I tend to inform myself as much as I can on the subject, but I found that having a dialogue with an expert works the best to unlock the whole thing. Because you can take another direction in a conversation compared to a scientific article that would have clear guidelines and is written in a different perspective than my approach to the topic. For example this project is linked directly to the history of botany, but brings questions regarding what the development of sea travels brought to us, and questions the economy of a country and what it implies in terms of biodiversity.

Clément Verger, Microscope view of a eucalyptus leaf.

E: The exhibited work is just part of a bigger body of work. How did you choose what was going to be shown in the exhibition?

C: The choice was made along with Maya Byskov, the curator of the show. It was quite complex as the project is vast and it is difficult to make it understandable in a few pieces. At the end, it is about finding a selection that function in a group show, in the space that was dedicated to my work. It would take a really different form in a solo show.

Because it will be quite rare to have the opportunity to show the whole project at exhibition venues, I created a document (a sort of folded leaflet) that contains the whole of the text and photographs organised around a diagram, showing the interconnections between the different elements of the project. For example it draws surprising connections between seemingly abstract elements, like an American space shuttle linked to a young Joseph Banks or to a plantation in southern Portugal.

Clément Verger, Sao Domingos Mine.

E: Some of your photographs are printed on newspaper

– what are your thoughts on the choice of paper?

C: The black and white prints are printed on newspaper paper that is made from eucalyptus pulp. Eucalyptus is planted for the paper industry and its main destination is to the newspaper industry. It was quite interesting to work on a paper that is not made for fine art photography printing and carries the culture and political charge of what a newspaper represent. The paper is 60g and really fragile. It took a lot of work and tests to obtain the quality desired. I worked with my good friend Juan Cruz Ibanez, who is a really talented printer and had the patience to really try different options.

Clément Verger, Botanic gardens of Coimbra.

Clément Verger, Swamps.

E: Can you tell me about the frames you made for the project?

C: It comes from the same reflections as with the choice of paper. If you look at a framed photograph most of the time what you see is an image, not an object. My aim was to introduce more levels of information than what you could directly see in the photograph. The paper tells you a story, and so does the wood of the frame. I designed and made the frames to be reminiscent of something half way between natural specimens boxes that you would find in a museum and the carpentry of a sailboat. They are made either from oak or eucalyptus wood – the oak frames are attached to photographs that represents elements before the introduction of the eucalyptus, and the eucalyptus ones for the post eucalyptus era. European oak was used for the construction of the Endeavour, James Cook's vessel, and is also a tree representative of the native Portuguese landscape.

I also wanted to experiment on producing a photographic work that, while still keeping a traditional form (a framed picture), has its own identity. I wished the frames to be unique for this work, and in specific materials.

E: Your awareness of materiality gives the project integrity, and makes it a unified whole. Is that a personal goal or is it somehow amplified in this project because of the theme?

C: It was definitely a personal goal, it would have been much easier to produce the work differently, simply printing it and sending it to the framer. But for me the materials used for the frames and the prints are as important as the photographs themselves. And there is something quite interesting in producing everything myself, especially for the frames. I spent almost a whole month working in the wood shop to do tries, improve the design and experimenting with the different woods. There is something really satisfying in putting the pieces together and finally see them live.

Clément Verger, The Transit of Venus across the sun observed from Tahiti on June 3, 1769.

The exhibition can be seen on Campus Bindslevs Plads, Silkeborg, from the 12th of November to the 2nd of December, 2017.

Emmali Sellner (f. 1992) er kandidatstuderende ved Æstetik og kultur på Aarhus Universitet. Emmali har bidraget til idoart.dk siden 2017.