AN IMPROMPTU CONVERSATION ABOUT WORKS IN PROGRESS, IN BODY, IN REFUSAL, IN HIDING

From the 11th of March 11 till the 10th of April 2022, the two artists crazinisT artisT/Va-Bene Fiatsi (GH) and Tore Hallas (DK) filled the artist-run space Galleri CC in Malmö. This article is based on a recording of a spontaneous conversation between the curators of the exhibition Shape/Build/Form, Arngrímur Borgþórsson and Maria Norrman, and Tore Hallas – a conversation revolving around fragile photographic techniques, fatness as a queerness and the act of saying no to societal expectations of productivity.

Maria: Maria Norrman, artist/curator.

Arngrímur: Arngrímur Borgþórsson, artist/curator.

Tore: Tore Hallas, artist.

Maria: You did this work as a test and it’s the first time it is shown?

Tore: Yes, outside of the art academy. It’s a technique that I found out about a long time ago, while I was studying, but it's the first time that I've shown the work outside of it. It's a technique that I took a long time trying to figure out what to do with, because I developed it before I found the thematics for the work, which is weird – I usually work the other way around.

It spent a lot of time in a drawer, but I knew I wanted to use it for something at some point. It was a vessel for something. I'm actually still not sure that this is the right thing to fill it with, but this exhibition is a test of trying to figure out what happens when I fill it with this theme that I'm working on currently, about fatness and queerness, different bodies and desire.

“It’s a technique that I found out about a long time ago, while I was studying, but it’s the first time that I’ve shown the work outside of it. It’s a technique that I took a long time trying to figure out what to do with, because I developed it before I found the thematics for the work, which is weird – I usually work the other way around.”

Arngrímur: That is surprising, because I felt that it was a natural progression of your work. I was just like, oh of course, when I saw it.

Tore: It is. But that's also because these are themes I’ve worked with for the past few years. It made sense to put that in there eventually, and it’s a natural progression of what I do. But I have also had several other subjects in my practice previously and concurrently, like religion, mental health, and photographic and filmic construction. And quite honestly, these things also came up in previous work, and were maybe overlooked.

The one present here is a photographic method – this meta photography. Photography about photography, and through that the form becomes the subject too. So yes, it’s a natural extension of what I do, but it was a weird one still, like it wasn't just photography – I had to really consider how this technique affects a subject. It was like having the melody, but no words.

Tore Hallas, Beholder Behold. Galleri CC, 2022. Photo: Sofia Wickman.

Maria: Where do you see it go from here?

Tore: One of the things I need is to make them permanent, because these works have a surface that you can't touch – you can't roll them or put them behind glass. You can't do anything with them, so everytime I exhibit them, I have to redo them, and I need to find a way technically for that not to be the case. This constant reprinting is really expensive and really time consuming, because of the special type of print.

Arngrímur: It’s a particular type of paper with a particular type of ink?

Tore: Yes, I mean, this is actually normal inkjet print, but the paper and printing processes are quite specific, and easy to fuck up. And it's actually a kind of shitty, cheap paper. But it has to be that specific, shitty paper, which took me like a year to find. And even then, when we found it, we had a lot of problems with it. It was a really fucking annoying thing.

First I was told several times that it was out of production. And then when I finally found someone who had it, he was like, “I just sold the last roll, I'm not ordering more, because it took me four years to sell 10 rolls.” So then I just had to tell him, “Okay, I promise you, I'm going to buy all your rolls, just please order.” But it’s very fragile – one fingerprint and it’s ruined. Ephemera and fragility is interesting, but it wasn't my intention here.

Arngrímur: Yeah, I don't think that the audience gets the sense, when they view them, that they are a one-time thing.

Tore: No. No, it's not there really. It has only been mentioned in the funding applications. It means I need more money, you know, that's the only place where I really talk about that part of it. It’s the practical side of things, which is annoying as fuck. And it made me acutely aware of the importance of considering and figuring out the permanence of a work.

“Yeah. It was quite funny. It’s just four squares on the wall. The room looks almost like nothing. And it will get very little traction on Instagram, because it’s just black squares. There’s nothing in it that draws people in. And to me, that’s really funny.”

Maria: At the opening you mentioned, that you sort of wanted the works to be kind of boring. Like some people would just say, “Oh, boring, black squares” and just pass them by. But then when you saw people passing them by, you had some feelings about it.

Tore: Yeah. It was quite funny. It's just four squares on the wall. The room looks almost like nothing. And it will get very little traction on Instagram, because it's just black squares. There's nothing in it that draws people in. And to me, that's really funny.

But then at the opening, I got my stupid, little feelings hurt when people didn't go up to them and spent time on them. It was really dumb because it was me enjoying that I really made it difficult for people to engage with it, and then get upset when they didn't engage with it. But then, when you actually engage, there is first of all the actual thematics of the work, but there's also the kind of humor of how they work as minimalist works in the white cube. I don't use humor a lot, but it happened on its own here.

Arngrímur: Maybe it will soothe the hurt a little bit, that during normal opening hours, people engaged with them differently than at the opening. They look at it much more closely, because they have come here not to drink wine or talk, but to come and to actually look.

Tore Hallas, Beholder Behold. Galleri CC, 2022. Photo: Tore Hallas.

Tore Hallas, Beholder Behold. Galleri CC, 2022. Photo: Tore Hallas.

Tore Hallas, Beholder Behold. Galleri CC, 2022. Photo: Tore Hallas.

Tore: That's nice! That engagement is important. Because this is one of those works where you don't really see it, unless you engage with it. I think we all know that kind of art that is just slightly challenging time and effort wise, is not art for an opening.

Maria: They also benefited from people talking and saying “Oh did you see the person in the square? Go back and look!” Then it became word of mouth.

Tore: Yeah. And I like that sudden feeling of “Oh shit, what's going on there?” I'm usually much more slow paced in my work, but that is a nice sudden reaction, that you have to work a little bit for.

Arngrímur: I think that the work has this quality of the Magic Eye prints – the 3D pictures. With the first print, the misprints, I thought, I'm just not seeing it – I just assumed that I was doing it wrong.

“One of the things that this work comes out of is my recent work with fatness and queerness – and how fatness is a queerness.”

Tore: Very much like Magic Eye.

One of the things that this work comes out of is my recent work with fatness and queerness – and how fatness is a queerness. While traveling a couple of years ago, before the pandemic, I started taking some photos of men that I had dates or hookups with, and having me and them naked, or semi naked, next to each other. And that's where this started. Because often the men, I'm with, have a different body type than mine – than my body type – and it was this kind of idea of how desire is skewed by who we expect people to desire, and who we accept as desirable people.

Then it kind of morphed into taking myself out of it. I might put myself back into it, but in this work I take myself out of it and just put those two bodies individually – a fat body and a non-fat body – in separate photos. That separation kind of removes the sexual aspect. It talks more about the body than desire. And I don't know where it's going to end up. Maybe it's going to be both. For these works I’ve hired models, which strongly separates this from the previous work in the series, where the relationship was more intimate. I don't think I'm going to discriminate what I put into this form right now, I'm just going to try out different things.

Arngrímur: Something you mentioned to me, when we were installing, was about this kind of forcing, in quotation marks, people to look very closely at fat bodies – I found it another fun aspect of it.

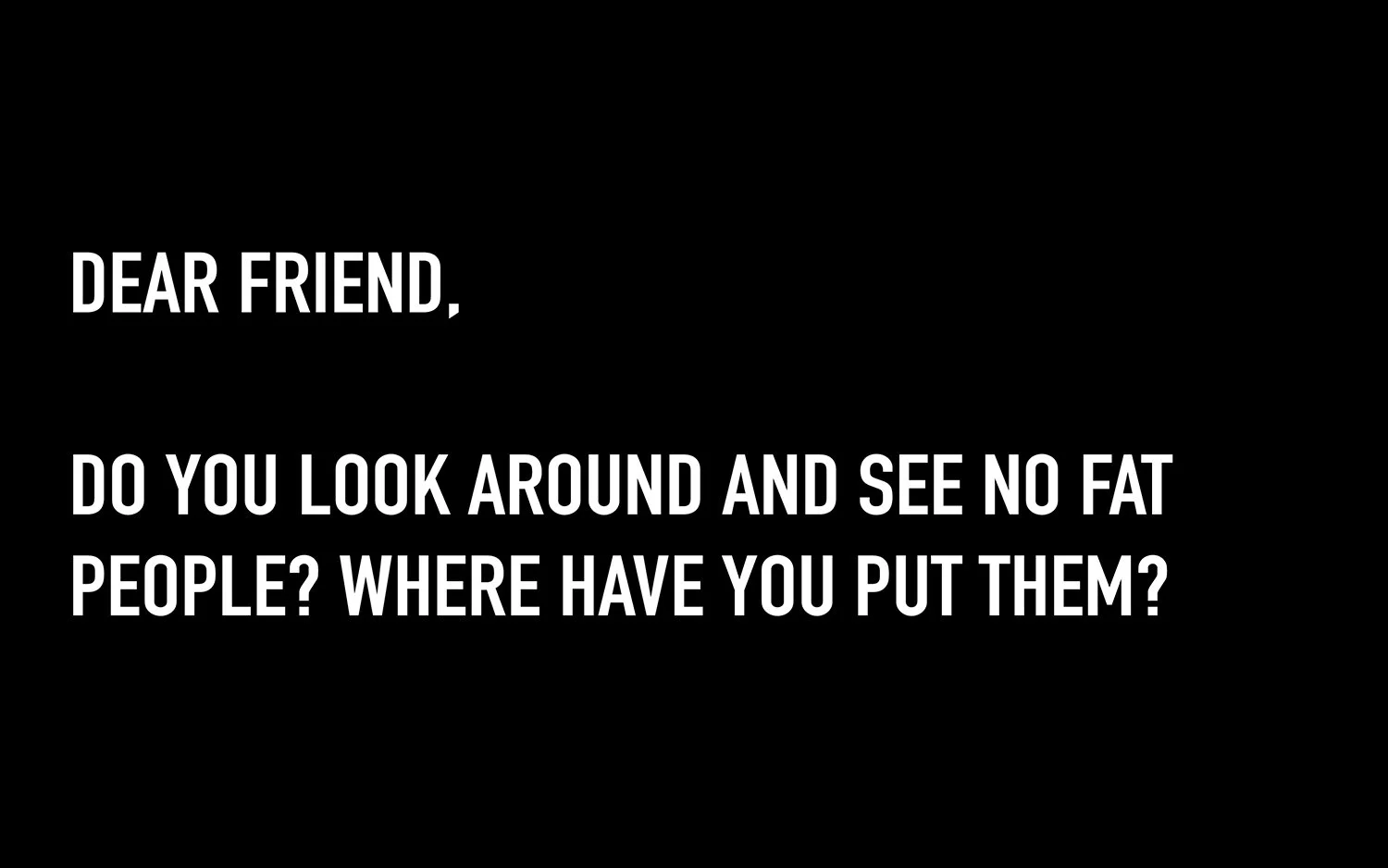

Tore: It’s connected to the fact that you have to work, to actually see it. And one of the things that gives me a lot of joy is forcing skinny people to look at fat people, and really work hard to stare at them, you know. Because everyone has been taught that we do not want to look at fatness.

“People actively or subconsciously reject fat people from their lives – we are inconvenient. So it’s fun to make those people, who might object to seeing that kind of body, make them actually see that body.”

I do work that delves into the discrimination of fat people, which is structural, systemic and social. This aspect you mention here is more about the body that you choose not to see, the body that you cut out of the group picture before you post it on Instagram. The body that you don't want to look at at the beach, even though there are some people that do want to look at those bodies at the beach. There's just a majority of people who decide what the acceptable body to be associated with is.

People actively or subconsciously reject fat people from their lives – we are inconvenient. So it's fun to make those people, who might object to seeing that kind of body, make them actually see that body. It’s like they're going to work really hard at seeing something, and then when it appears, they realize what they've been working hard to look at.

Tore Hallas, Beholder Behold. Galleri CC, 2022. Photo: Tore Hallas.

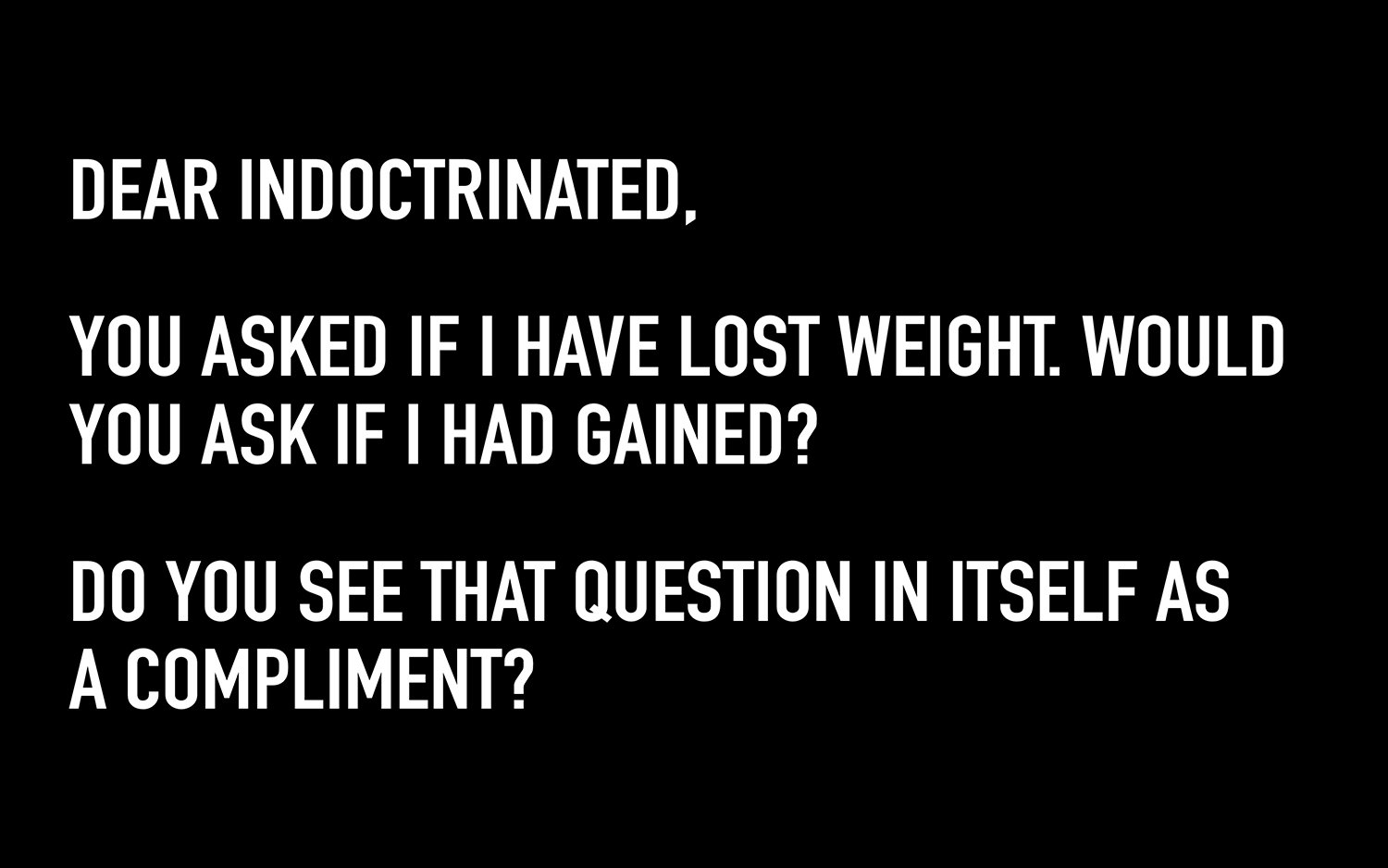

Maria: Can you talk about the other work in the exhibition, called No.?

Tore: The title is actually one of my favorite parts of that whole series. It's a series of poems that originally was just the seven poems, but I'm starting to think of them as an ongoing project. I think there's a lot of potential in talking about refusal. Of course it references Bartleby the Scrivener – it's this refusal of participating in the things that are required or expected of you. And saying no to this performance society that we have, that some people are not comfortable in, some people cannot participate in, and it makes people sick. I have some personal experience with that, and with my family and friends. Some people just don't, just cannot, just don't want to.

All the poems directly address some form of concept relating to that. One is addressed to a career opportunity. I'm depressed, and so I'm in bed, and I'm working on a work that is about depression, about being in bed, but I'm not working on it, because I'm depressed, so I can't answer that email, where you're asking me when the work about me being depressed is done, because I'm depressed. It's this constant circular movement. The work itself is the reason why I am not able to finish it and meet the deadline. The reason you hired me, is the reason I'm not finishing the work you hired me to do.

Tore Hallas, No. (Still), 2021.

Tore Hallas, No. (Still), 2021.

And that's kind of where it started, because sometimes I just don't answer emails for a bit. And that's not healthy for your career, but it's a defense mechanism. So half the emails I write, I start with an apology. And then comes the bruising, that this kind of society gives people sometimes, when you're dragged through it, when you're forced to participate.

A lot of opportunities that I've had, haven't gone anywhere, because I couldn't catch it at the right time, or I couldn't live up to the expectations of whatever the opportunity required. Or I wasn't the right fit personally, or personality wise, because they needed someone who had a certain type of energy, and I didn't have that energy because I had a bad day and wanted to go home and you know, just lay in bed for a week, or I had an anxiety attack or whatever. Why are we required to be certain ways to just be able to have a career and exist and not be completely obstructed in life? The work kind of expanded from there, and it's open still.

Tore Hallas, No. (Still), 2021.

Maria: It's tragicomical. This poem that you were talking about, where the work is about the sickness of the mind, and “Me not answering your email, is me not going to work.” There's some fuck you humor in it, that I really like.

Tore: That's kind of true. It was written out of frustration about missing an opportunity, because of what I was going through. But then it also developed into anger. Anger about what is expected of us, and what happens to people who cannot live up to those expectations.

Maria: It's upsetting for us as artists, but can also relate to everyone else.

“I had this thought of people biking in the winter rain, and everything sucks, and they’ve been up too early and it’s pitch black, and all the other bicyclists are annoying. And you’re annoyed with this requirement. And then you see this big “NO.” that you just might connect with.”

Tore: I was really happy when the work was first exhibited. It was in a public space and the title card for it was in this square in Copenhagen, where a lot of people bike through every day, every morning on the way to work, and every day on the way home. I had this thought of people biking in the winter rain, and everything sucks, and they’ve been up too early and it's pitch black, and all the other bicyclists are annoying. And you're annoyed with this requirement. And then you see this big "NO." that you just might connect with. A couple of blocks from there, you could see the actual works, the poems, and they required a little bit more. They required you to just take a moment. And the thing here – in this gallery context that we are in now, where it's a slideshow, is that I've made it, so that the title card comes up between every poem. Because the title is such an integral part of the work, that it becomes this reminder of what it's about. With the poems being branches of aspects of that, reasons to say no. And here’s another wound that comes from not saying no, and another trauma that the world doesn't accept no’s have caused you. I like the slideshow here, because the title becomes part of the work in a very active way that it wasn't originally – it was in a separate location, which had other advantages.

Tore Hallas, No. Til Vægs, 2021. Photo: Tore Hallas.

Maria: Were there any reactions when the exhibition was on display in the public space that you've heard of?

Tore: Yeah, public art as a genre is strange to me, which is why I was happy to do it. It reaches people, who don’t normally seek out art.

One that stands out was this woman, who was just passing by, came up to me at the opening and was really affected by it, by the poem about scraping against the asphalt, and she asked how I could put these things in public – they are so hurtful. And, as opposed to the black squares, these got a lot of reactions and stuff on Instagram. And with the black squares, I really like that you have to show up for it, but with NO. I like that it’s living online too. There’s so much art that lives mainly on Instagram, and I see the advantage of that, but something else happens, when you show up. Clearly.

Tore Hallas, No. Til Vægs, 2021. Photo: Nils Elvebakk Skalegård.

Arngrímur: In the slideshow installation, you're also again forcing people to stand there, because you have to wait for the different slides.

Tore: I sometimes get the urge to make work that I myself don't have the patience for. I don't have patience to look at a slideshow if you haven't timed it right. But I also have the instinct to time these way too long. And make it way too slow, just to annoy people like myself. Which I guess goes with the concept about general disobedience, general arms crossed vibe.

Arngrímur: I also like that it reminds me of these motivational posters. It's something about the format, you know, those posters of "be your best self".

Tore: Yeah, a kitten hanging onto a branch, and it says "Hang in there!" Don't hang in there. Fuck that kitten.

Arngrímur: The motivational posters really don't give you anything. Just a [shrinking sound] of “Buddhist wisdom”.

Tore Hallas, No. Til Vægs, 2021. Photo: Nils Elvebakk Skalegård.

Tore: But here it is a [shrinking sound] of hurt and trauma caused by a society that applauds motivational thinking. That has created concepts like motivational posters. It's actually a really good reference, that I had not thought of myself, because they are cutesy but evil representation of exactly the kind of thought process and work ethic and general ethic that I am presenting a counter-thought to. No, you shouldn’t have to fucking hang in there. You should be allowed to not hang in there.

“I do not want to be cutesy in this work. If you laugh from these works, it is because it’s really recognizably painful and you have to laugh to defend yourself.”

And I do not want to be cutesy in this work. If you laugh from these works, it is because it’s really recognizably painful and you have to laugh to defend yourself. It took a long time to define the wording of the individual works, because it is a fine line. So maybe it's not unfunny, but it's also not funny.

Tore Hallas (b. 1984) is a visual artist, living and working in Copenhagen, Denmark. Tore holds an MFA from The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Visual Arts, 2019.

Maria Norrman (b. 1987) is a Swedish visual artist with a MFA from Malmö Art Academy, 2013. In 2022 Norman is a part of the gallery committee at Galleri CC, Malmö.

Arngrímur Borgþórsson (b. 1979) is an Icelandic/Swedish visual artist with a BFA from the Iceland Academy of the Arts (2006) and an MFA from the Umeå Academy of Fine Arts (2013). In 2022 Borgþórsson is a part of the gallery committee at Galleri CC, Malmö.