Kristina Bengtsson & Michala Paludan, Soft Layers (Installation view). Photo: Cian Burke.

Press Release, September 2020

At a time when photography is once again going through radical changes propelled by technology, Bengtsson and Paludan’s exhibition Soft Layers uses the history of photography as a starting point for discussing where it is potentially heading. Much in the same way that the portability of 35mm cameras drove a whole new way of seeing the world, such as The New Vision movement of the 1920s, digital technology has changed and democratized both the way we use and consume the medium today. Soft Layers addresses photography as a language in constant flux and raises questions about what is lost and gained with each new shift in its vocabulary.

Alongside her practice, Kristina Bengtsson has worked as a printer at various photo laboratories around Scandinavia while in recent years, Michala Paludan has taught photography theory and history. The intersection between these two personal perspectives, with an intimate understanding of the medium, is where this exhibition takes its starting point. Bengtsson works with photography, sculpture and text. With sociology as her main area of interest she often uses everyday objects in combination with pop-cultural references as a way to activate a critical engagement around representation and understanding. Paludan works with photography, installation and text. Her work often centres on issues around power – how it is produced, manifested and negotiated within the political landscape. In her project presented at Format Paludan uses her own personal history to reflect upon family, photography and power.

Kristina Bengtsson, Appendix, 2020 / Frontier, 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

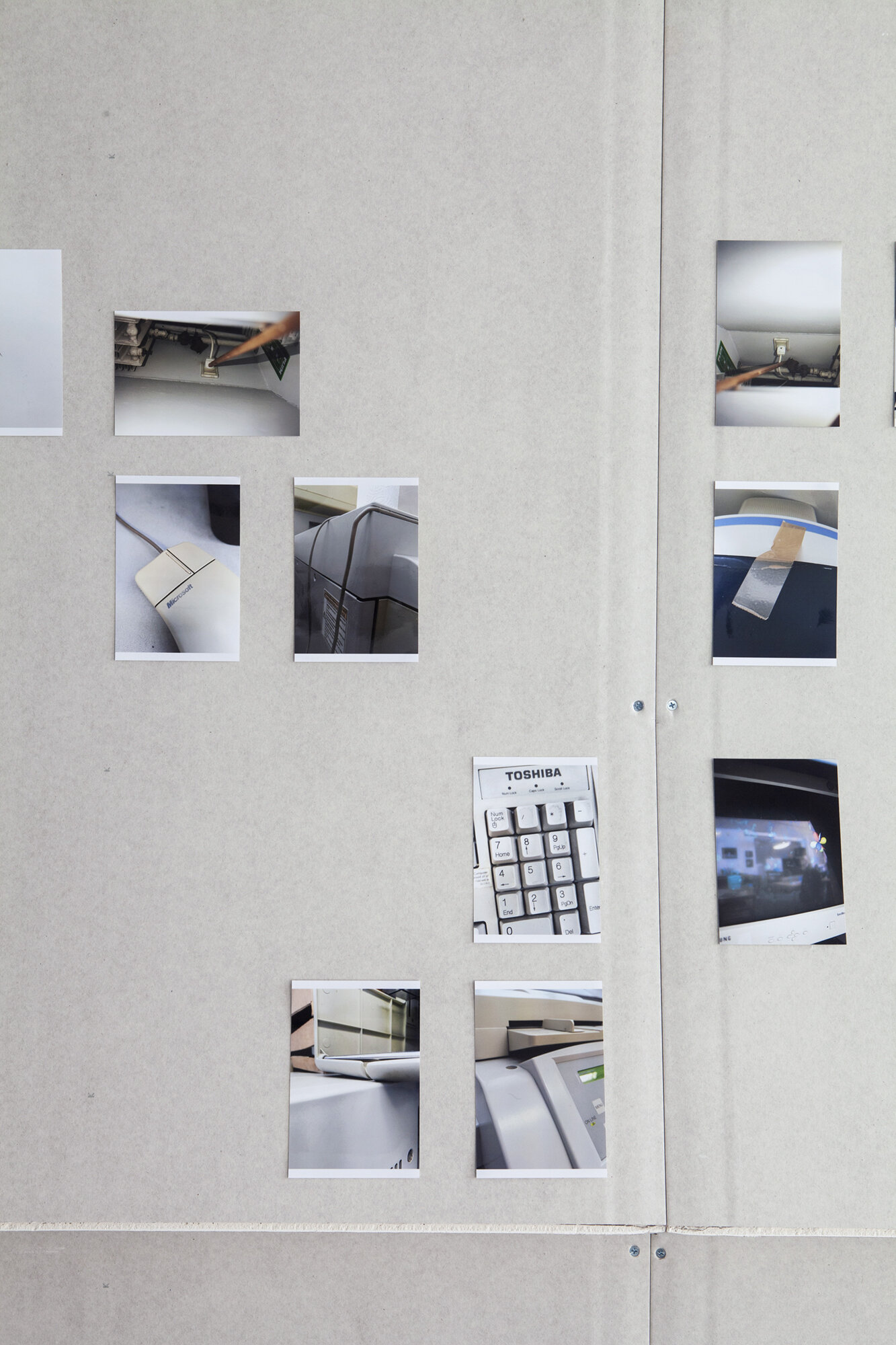

Kristina Bengtsson, Frontier (detail), 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Kristina Bengtsson, Frontier (detail), 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Kristina Bengtsson, Appendix, 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Kristina Bengtsson, Appendix, 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

During the exhibition Paludan and Bengtsson will be inviting the public to partake in three group reading sessions hosted at the gallery. During these sessions they will examine three key points in the historical development of photography and jointly discuss various positions and movements within this. Each session will be led by Bengtsson and Paludan who will make use of the works in the exhibition as references and anchors for the discussion. Each session will take approximately two hours including a break. Throughout the exhibition period the texts will be available to read at Gallery Format and after each session notes from the group readings will be added to the texts.

The reading group sessions will take place on the following dates:

Saturday 26th September at 2 pm.

Thursday 8th October at 6 pm.

Thursday 22nd October at 6 pm.

Opening: Thursday the 24th of September, 12-8 pm.

Exhibition period: 24th of September - 8th of November, 2020.

Opening hours: Wed-Thu: 2-6 pm, Fri: 11 am-4 pm, Sat-Sun 12-3 pm.

Kristina Bengtsson & Michala Paludan, Soft Layers (Installation view). Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, Untitled (Malcolm, Janet, Diana & Nikon, expanded edition p. 175) / Untitled (Sontag, Susan, On Photography p. 8) / Untitled (Wang, Esmé Weijun, The Collected Schizophrenias p. 164) / Untitled (Mersal, Iman, How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts p. 57) / Untitled (Mersal, Iman, How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts p. 58), all 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, I.F. (portrait of my father). Photo: Cian Burke.

Reproduction at the frontier

By Kevin Malcolm, Copenhagen, 2020

One of the primary uses of photography has always been the documentation of loved ones. A vast multitude of film rolls and memory cards have been filled with images of family, friends and lovers but also of places and objects. People and things we care about enough to want to have pictures of them. It may bring us closer to those loved ones but photography can also be a way of engaging with them from a distance. The camera can be used as a technological apparatus and a time travel device with which to be in the moment while actually avoiding it at the same time. A kind of comfortable detachment, keeping people and things at arms length. A tool with which to make documentary proof that you were there, while using it to avoid being totally present. As the preeminent artist-photographer-of-loved-ones Sally Mann herself states: “Maybe this could be an escape from the manifold terrors of child rearing, an apotropaic protection: stare them straight in the face but at a remove—on paper, in a photograph.”

In Paludan’s work the artist photographed as a child by her photographer-father becomes the photographer- mother who photographs her own children. Parents are expected to photograph their children enough that they seem sufficiently interested in them but not so much as to seem obsessed. This is the difference between the everyday practice of people photographing their children and doing the same thing but as an artist. With the intention of printing the photographs and exhibiting them publicly, to an audience. To be doing this as a job, maybe even to make money off it.

To move, and move with, these images through the channels and structures of the contemporary art world is a different game entirely from making holiday snaps of your family that only your family will see. (There is one other person who sees them all but more about her later.) There are so many layers of meaning and relationships and difficulties, so fraught are the tensions and anxieties that we must wonder what the point is, what is really being represented. These kind of photographs are often not just about the people and objects in them but also, and probably more so, about the person who made them. We might instead be looking an expression of the need to make these images and of the desire to take that space, to occupy that position. To carve out a place and time for oneself to be a photographing mother who was once a photographed child, on one’s own terms. To repeatedly demand the right to relate to one’s craft and one’s family and one’s motherhood however one chooses and to be as unapologetically dedicated and professional about it as one wants.

The unfortunate irony is that the average phone camera wielding parent probably makes many, many more images of their children than Paludan does, or Mann did for that matter, its just that they take it less seriously, spend less time doing it, less time thinking and writing about it. The fact that these artist-mothers even need to justify it to themselves and others shows how persistent is the internalisation of a photo-patriarchal panopticism that would have them wonder if their practice is indeed too much, while a male-identifying artist can simply get on with photographing whatever-they-damn-well-please with little or no existential introspection at all and very little expectation to justify it to anyone else.

Working as she does as a printer at one of the few remaining photo labs, it is Bengtsson who sees all the images made by the photographing parents, from the blasé to the obsessive. She colour-corrects, adjusts highlights, adds sharpness and perhaps crops them a little, all these images constantly flowing through the lab. When shot on film, each roll includes the outtakes and the bad angles. She sees them all, printing the misses as well as the hits. These days they are mostly edited, the misfires deleted from cameras and phones before being sent to the printer.

They are no less photographs because they are digitally captured, still a rectangle of paper exposed to light and chemicals that has a likeness of a part of the world on it. It’s difficult not to wonder how it would affect her visual sensibilities, scrutinising and printing other people’s photographs, a caretaker of images, lovingly enhancing the memories of strangers. It is as much an artistic practice in itself as it is a job. What does it mean to have many thousands of images passing before the eyes and through the hands?

The aptly named Frontier lab, once vanguard, now decidedly rearguard, has fallen out of time but is still relevant as way to produce the sought after wet prints in a fast and affordable way. It is a machine but it is not truly automated, there is no algorithm making decisions. Each and every print that it produces looks the way it does due to decisions made by the operator. There is no longer an education for this craft, the only way is to learn from someone else who already knows and from the machine itself. You could read the manual and see how it functions in an ideal situation but as to how it actually works, intuition and a level of mutual understanding are essential. It is with frustration and respect that one must relate to an ageing and ailing machine and vocation, still functional but eccentric and anomalous, prone to leaks and always thirsty but still pumping them out. You must work together and become friends, or at least amicable colleagues, relying as you do on one another.

One way of thinking about both of these bodies of work is that they are reproductions of reproduction. Producing offspring and pictures of them, like your parents before you. Producing pictures of the apparatus of producing pictures, caring for the ageing machine. Bengtsson and Paludan met each other while studying photography but neither would define themselves as photographers. Cameras have been lifted and shutters released, as we can plainly see, negatives and pixels have been exposed and chemicals have gurgled but to only view their practices as Photography is to not see them in their entirety. These are the works of photographing-sculptors, printer-poets, artist-mothers. Their practices and output make accessible to us the tensions and relationships between the worker and the machine, the artist and the worker, the artist and the machine, between the master and the apprentice, the father and the child. Between the mother and everything.

Kristina Bengtsson, Nah, 2017 / Dunno, 2017. Photo: Cian Burke.

Kristina Bengtsson, Maybe, 2017 / ish, 2017 / Sometimes, 2017.

Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, What Remains #1-8, 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, What Remains #1-8 (detail), 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, What Remains #1-8 (detail), 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.

Michala Paludan, I.F. (the self portrait) / Untitled (Mann, Sally, Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs p. 114) Untitled (Mersal, Iman, How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts p.43) / Untitled (Luiselli, Valeria, Lost Children Archive p. 42), all 2020. Photo: Cian Burke.