THIS IS NOT AN APRICOT: IT TAKES ONE TO KNOW ONE

I never thought I would be asking myself this question: what are the similarities between fish and me? The question emerged after I met the Chicago based curator Mary L. Coyne to talk about her recent exhibition – This Is Not an Apricot, featuring artworks by Keren Benbenisty, Runo Lagomarsino, Candice Lin, Pia Rönicke, Terike Haapoja and Laura Gustafsson, which is currently on view at SixtyEight Art Institute.

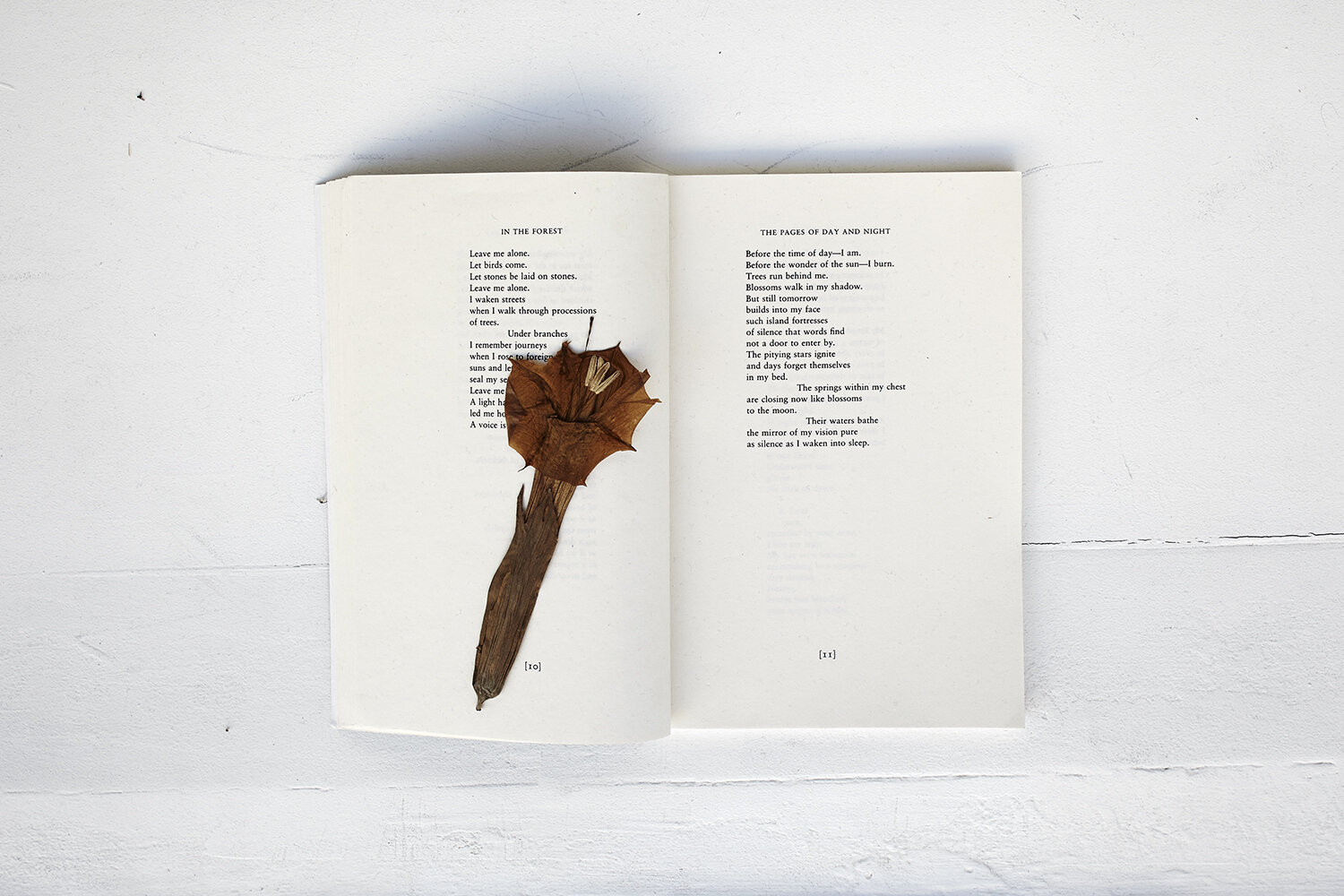

Coyne and I agreed to meet before the opening of the show. I arrived a bit earlier and ended up standing in front of SixtyEight peeping through the window, where a poetry book is on display.

The book is open to The Pages of Day and Night, a poem written by Syrian poet Adonis. A pressed flower is carefully laid on top of the poem, fuelling beautiful imaginations around the possible interlaces between nature and culture. Leaving with this initial impression, I went to have a chat with Coyne that began with her view of Nørrebro and migration in Europe, neighborhoods in Chicago and the development of her ideas around the exhibition, which shed more light on the context of the exhibition.

Pia Rönicke, Adonis – The Pages of Day and Night, The Marlboro Press / Northwestern, 1994, Lathyrus pratensis (2015). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

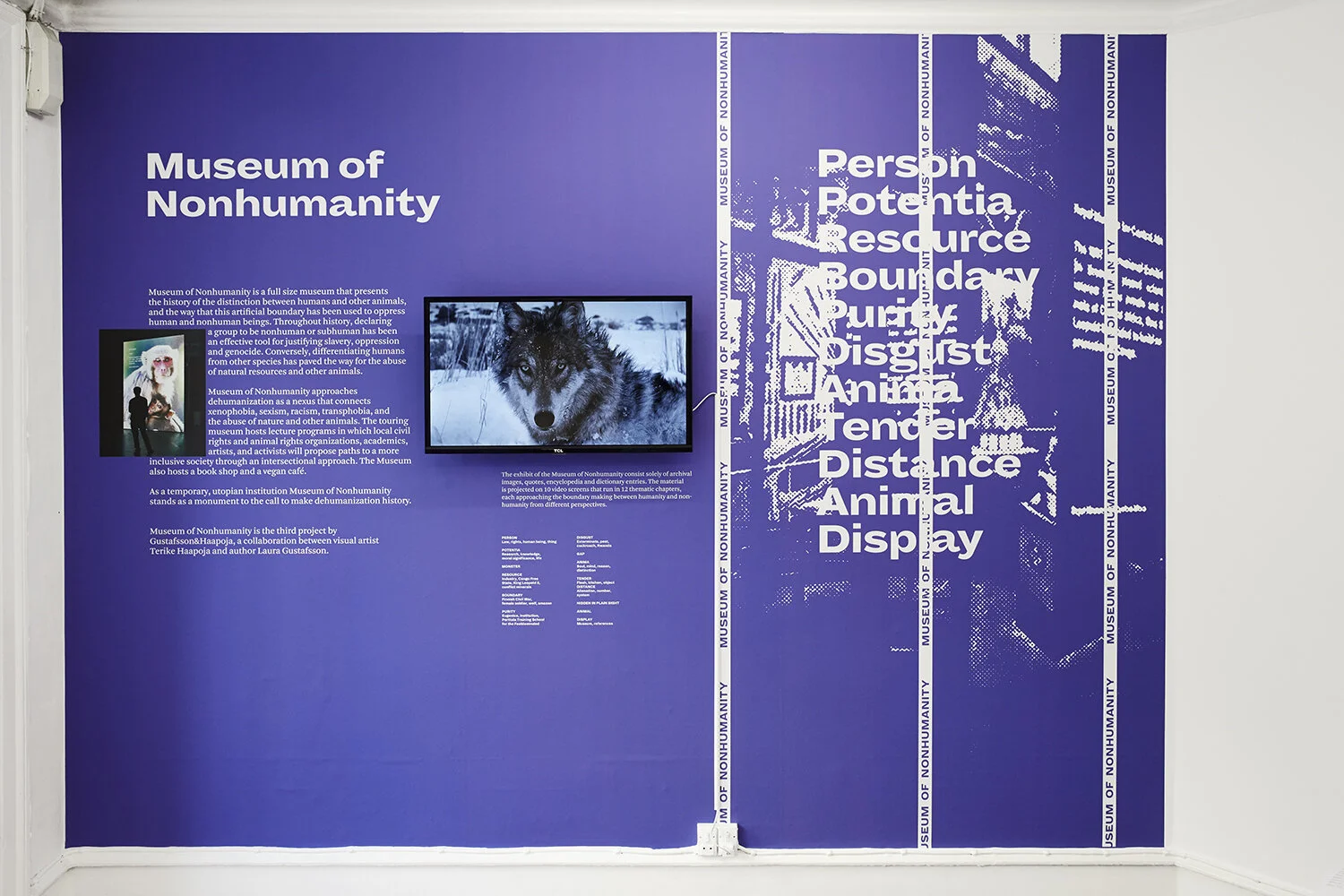

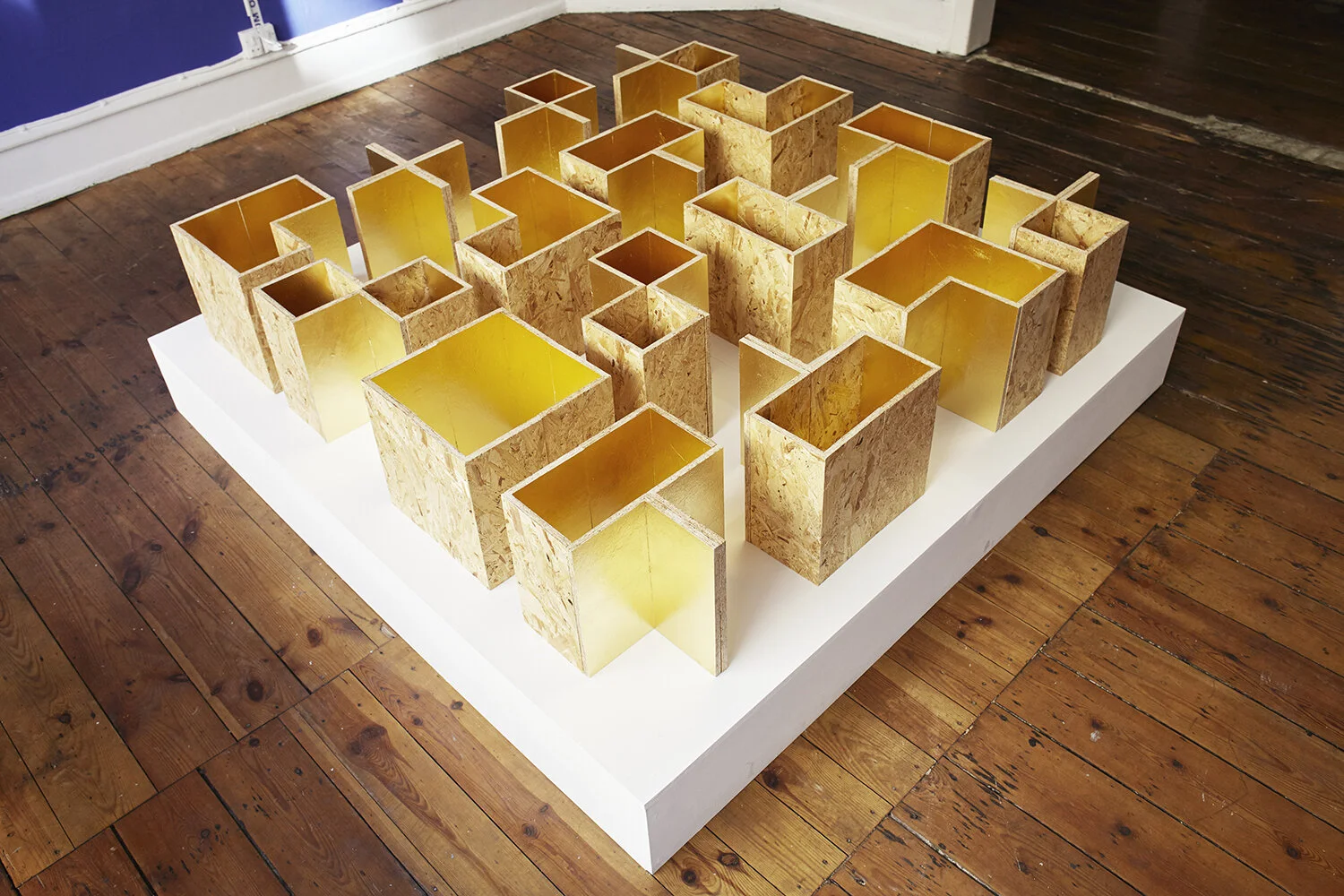

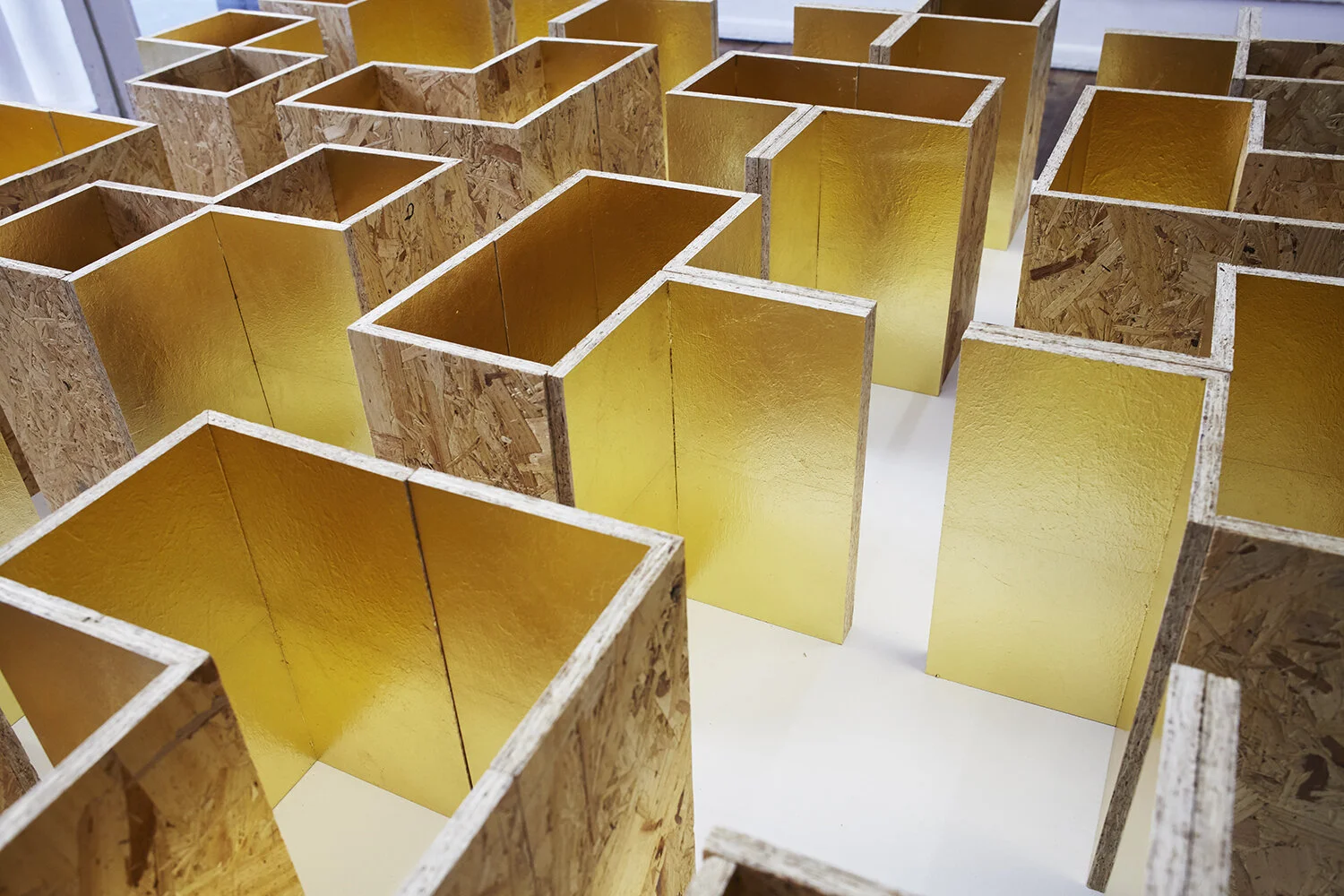

Returning to SixtyEight we continued the journey and talk inside the exhibition. Elements of nature and culture continue to mingle (and present themselves) with a hue of declining human warmth and affection. This only creates an increasing sense of objectivity in the artworks' visual and textual embodiments. Looking around the main room, which has been painted purple, modular rectangles made of plywood and gold foil are thoughtfully arranged into a matrix on a white platform. Looking up, texts that are titled “Museum of NonHumanity” cover the whole wall and surround a screen of rotating definitions or quotes on terms such as person, monster, or animals. Opposite hang shadowboxed collages of text, images and decaying organic materials, weaving a narrative that is rather strange and unfamiliar.

This Is Not an Apricot, Installation view. Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Away at the dark end of the space is a video in which specimens of fish are inked, measured and skinned, with a biologist’s narration in the background relating the history and biological consequences of the migration of these fish through the Suez Canal between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. Adjacent to this video by Keren Benbenisty, the skins of the specimens are projected onto the wall, as if they are being viewed under a microscope.

Keren Benbenisty, On Black & White (2016) and Light Skin (2016). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Surely none of the artworks are, or is about an apricot; they are flowers, seeds, fish and gold. But can we really see nature that consists of flowers, seeds, fish and gold as what it is? This is a question the exhibition tries to answer, or at least challenges the viewer with.

The title of the show, This Is Not an Apricot, taken from the Brazil-born conceptual artist Maria Thereza Alves’s work (2009), indicates a cultural semiotic approach to the human-nature relationship where “nature is […] a strongly culturized and at the same time relativized referent (since ethnotaxonomies give different ‘visions of the world’)”.(1) By reflecting on nature’s constitution as discursive in the histories of colonialism, sexism, and many other kinds, “the exhibition interrogates critically the knowledge humanity bases its critical discourse on – which often is institutionalized as the bedrock for systemic and oppressive colonialist beliefs”.(2)

Coyne has mapped out one particular position of time and space for viewers to reflect upon this nature-human relationship. Such as Europe’s refugee crisis from 2015 onwards, where hundreds of thousands of people fled across the Mediterranean Sea to escape war and persecution. The migration of human beings has caused fear and prompted a stormy political debate for the human world. But what about the migration of non-human beings, such as animals, plants, or minerals, which move via a similar (enough) route?

Keren Benbenisty, Light Skin (2016). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Returning to Keren Benbenisty’s work Light Skin (video), a biologist provides a paradoxical account of thousands of species of fish that migrated via the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, while the artist focuses on the ink, the measurements of fish specimens and their skin. On the one hand the biologist acknowledges migration as a way of living or as “natural phenomenon” that is not only seen among humans, but also fish and bacteria. On the other hand, in bearing a striking resemblance with the present-day political debate on migrations, the biologist emphasizes that the pace of migration in the Mediterranean Sea is “rising and alarming”. Although migration has “added colors to the Mediterranean Sea” and made it more “beautiful and interesting”, it is “not a positive phenomenon”. This paradoxical account of migration contrasted with the projection of fish skin in Benbenisty’s other work On Black and White, manifests further the deceptively clean-cut and non-subjective format of knowledge about fish as natural material by science.

Keren Benbenisty, Light Skin (2016). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Keren Benbenisty, On Black & White (2016). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

While Benbenisty’s works reveal how colonialist belief systems have not only shaped contemporary politics but also our biological arguments regarding animal migration; Pia Rönicke’s work The Pages of Day and Night reflects on how Western political anticipation has actually driven the migration of seed banks from the Syrian city of Aleppo to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. Such contrasts challenge viewers to ponder the question whether the scientific knowledge of nature as we know it today is a code of an unshakable law that we have unveiled, or a code of normalization that we, as humans, have co-produced in particular times and places through each status quo fostered by techno-scientific practices.

Pia Rönicke, The Pages of Day and Night (2015). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

One may also ask: who are the subjugating and subjugated actors in knowledge co-production? and for that matter, what happened to the subjugated actors, be they human or non-human? Turning to the gender divide in knowledge co-production, Candice Lin’s works Cannibalizing Cultural Memory and Animal within the Animal restore the voice and presence of women, who have been historically subjugated in the production of scientific systems of classification, by manufacturing fictional archival displays that interrogate how easily we accept taxonomies as knowledge.

Candice Lin, Cannibalizing Cultural Memory (2015) and Animal Within Animal (2015). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Focusing too on the legitimate formats of knowledge via display, Gustafsson & Haapoja examine the role of museums in shaping public understanding concerning different formats of knowledge – a role that particularly presents itself as “truth”. In their work Museum of Non-Humanity, although presented in a much-condensed format, Haapoja & Gustafsson provide an apparatus to cut through the normative construct of knowledge about nature and culture by making explicit a list of definitions that concern the way in which we often associate with nature. In doing so, Haapoja & Gustafsson also bring forward the political and cultural nature of language in reproducing hegemonic imaginaries of nature, which we may not be fully aware of.

Haapoja & Gustafsson, Museum of Non Humanity (2017-present). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

It seems, finally, that only with non-scientific instruments and methods may there be chances for generating new ways of knowing and new formats of knowledge – one that may be regarded as “subjugated” or “disqualified” as Foucault would call it, and one that can take the forms of fictions, or art itself. Runo Lagomarsino’s work Violent Objects seems to entertain a similar idea. He refuses to present purity as the only way to know and measure gold in both the scientific and commercial world. Instead, he offers a temporary account of a gold object that can vary. The production of subjugated knowledge can also be found in Candice Lin and Benbenisty’s work. In the latter I can’t shake a connection with the traditional method of Japanese ink printing – gyotaku (魚拓) and the idea that when we visit Natural History museums, we rarely see these prints that capture the generation of bodies and non-scientific technologies take center stage. Instead, a self-righteous form of knowledge often prevails in the museum, which presents itself as 'natural' and unmediated by human beings, but in fact perpetuates the same fake news discourse affecting Western politics today.

Runo Lagomarsino, Violent Objects (2014). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Along these lines, the exhibition This Is Not an Apricot offers a critical and revealing account of nature that is not the “other” that offers origin, replenishment and service, but strictly a “common place” for both human and non-human beings to rebuild public culture, including science (3). Each takes on its own perspective; the artists examine the scientific knowledge of nature that appears to be direct, immediate and truthful, and bring to light its position in particular times and places.

Runo Lagomarsino, Violent Objects (2014). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

Runo Lagomarsino, Violent Objects (2014). Photo: SixtyEight Art Institute, 2019.

In doing so, this exhibition pushes the viewers close to the ragged boundaries of their own knowledge territories. It provides a moment of pause for the viewer to observe the resemblance between the human and non-human world, one which invites critical thinking on many taken-for-granted systems of categorisation and classification, which we use to build our knowledge base on. It also provides viewers with tools to interrogate and create cracks in their very own knowledge base and logics, calling for projects that generate new forms of knowing.

To this end, in returning to the question at the beginning, what are the similarities between fish and me (or any viewer)? The deconstruction of ideas of a timeless and flourishing non-humanity, such as the fish, mirrors the deconstruction of a timeless and natural humanity, that is me. The exhibit leaves me wondering whether the path to understanding fish is the path to understanding myself and the very assemblage of my (our) own knowledge base. Indeed, this is not an apricot. It takes one to know one.

This Is Not an Apricot at SixtyEight Art Institute

on view till September 28, 2019.

Courtés, J., & Greimas, A. J. (1982). Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 375.

SixtyEight Art Institute (2019). This Is Not an Apricot.

Haraway, D. (1992). The promises of monsters: a regenerative politics for inappropriate/d others. Cultural studies, 295-337.

This essay is part of an initiative to foster Danish and English Language critical writings from a range of new talents across the visual arts; and as a partnership between I DO ART and SixtyEight Art Institute.

Cancan Wang holds a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Fudan University, China, and a master’s degree in applied cultural analysis from University of Copenhagen, Denmark, through which she cultivated a broad range of intellectual interest in topics such as love, gender, technology and art. Pursuing her interest in art criticism comes from her work in information technologies and their impacts on social relationships, which she organized into a Phd in the field of information systems from Copenhagen Business School, Denmark. Cancan Wang works as an Assistant Professor at the IT University of Copenhagen and is based in Copenhagen.

Cancan has contributed to idoart.dk since 2019.