THE CODE – AN EXHIBITION COMPANION TO FILIP VEST'S "FILMKYS"

Filmkys (Movie Kiss) is a performance and exhibition by artist Filip Vest about cinema, desire, intimacy and our oversaturated and deficient language for love. It’s a project about clichés, fake kisses on the screen and hesitant kisses in the dark, about which roles we cast and miscast each other as in the film, we call our life.

At the opening a performance took place, where people reenacted famous movie kisses. The exhibition also consisted of different sculptural elements and architectural interventions: pools of soft drinks and red carpets holding hands. During the exhibition period a film was screened in the cinema about all the things that happen in the dark, while the movie is running. The exhibition was originally developed for the opening exhibition of the new exhibition space Foyer Contemporary that inhabits the foyer of the cinema, Park Bio. In November, the project was remade for Celsius Projects in Malmö as part of the program Proximity by Proxy.

In connection to the exhibition Filip Vest invited curator and writer Håkon Traaseth Lillegraven to write an exhibition companion. This is his essay The Code, a text about movie kisses and queer cinema.

Filip Vest, Filmkys performance. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

THE CODE

An exhibition companion

1st score: Notorious (1946-2022)

My favourite kiss on film takes place at approximately the mid-point of Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Notorious’ from 1946. It’s an incredibly normative kiss but then again, as a gay movie-watcher I’m conditionally inclined to project my desires onto Ingrid Bergman as her and Cary Grant share a few devastating moments on a balcony somewhere in a Hollywood staging of Europe. I think it’s in Nice, France, but it doesn’t matter, what matters is how we imagine Nice, France to be. Lots of people have never been to Nice, but a lot of people have kissed. Imagine my pleasure when I learned that my favourite kiss is also implicated in some quintessential film history. The scene is an example of the (gendered) politics surrounding kissing on film, at least in the dominant Hollywood studio system of the 20th century. The reason Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman’s characters’ passion for each other is not consumed more embodiedly and without interruption is due to the Hays Code, a self-imposed industry set of guidelines for all the motion pictures that was enforced from 1934 until 1968. As part of this body of regulation, rules to avoid depictions of “excessive and lustful kissing” were in place, the unofficial rule being three seconds of prolonged kissing maximum.

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

Historically, the Hays Code reflects a return to conservatism after the increasing sexual liberation and even “queering” of cinema in the 1920s, where openly queer directors such as Lois Weber could direct films which “code-stretched” and played with conventional gender dynamics and suggestive romantic pairings. The introduction of the Hays Code meant that even depictions of the most conventional forms of love was strictly regulated, leading to the depictions of even monogamous, heterosexual partners sleeping in separate bedrooms for decades to come, at least on celluloid. The kissing scene in ‘Notorious’, which goes on for a total of two minutes and fifty seconds, lives up to its title by being a masterclass on how to realistically portray unconsumed desire while side-stepping the formal regulations which could have forced it to be re-edited or re-shot.

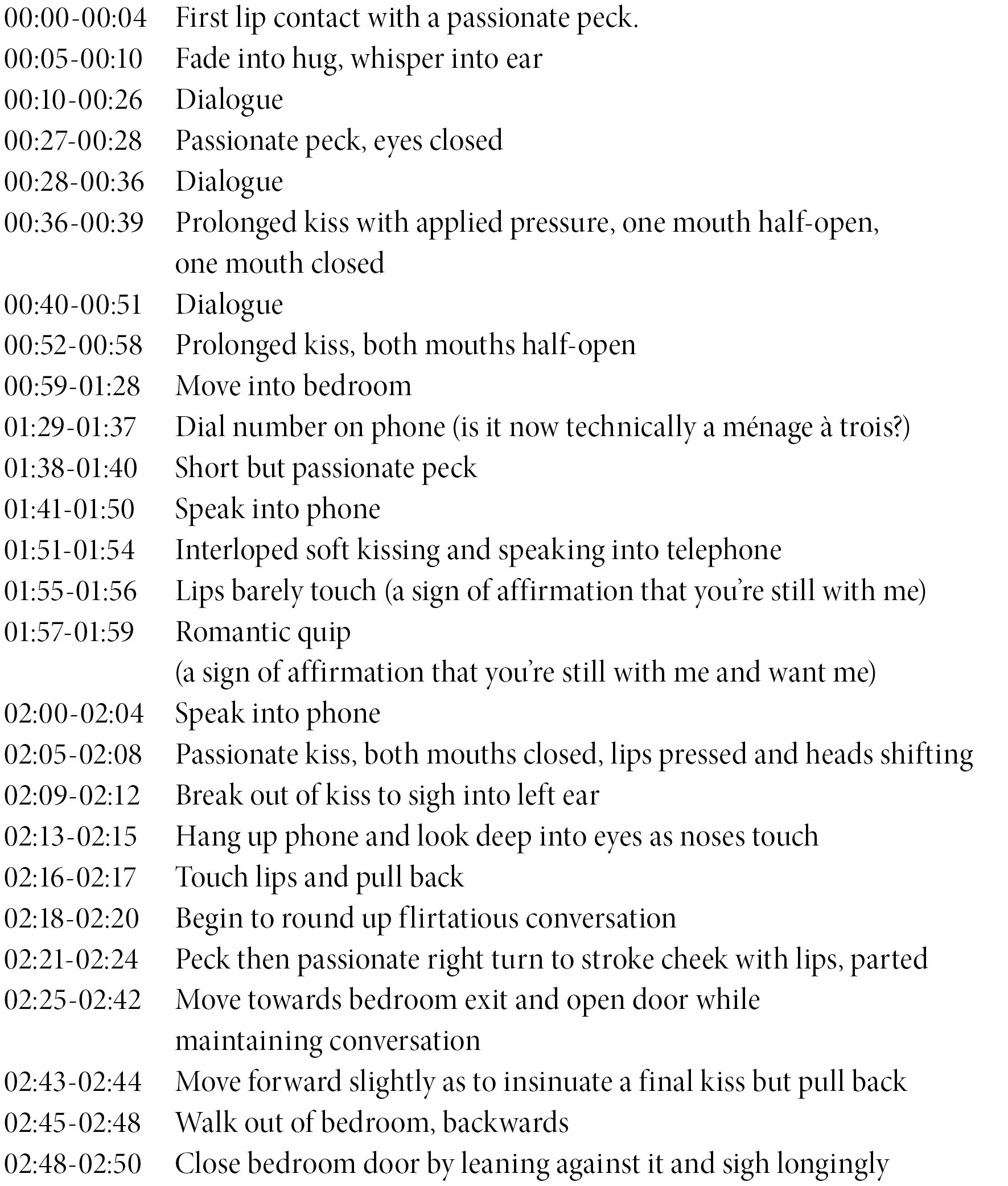

The score of the kiss could be written down approximately as such:

2nd score: Peep show

American film director Sydney Pollack once said something like: “You can show people falling in love for 2 hours, and people falling out of love for 2 hours, but you can only show people being in love for 2 minutes.”

Amongst the first historical records of the moving image experiments which preceded narrative cinema is an 18 second clip of a man and a woman kissing, produced in 1896. Simply titled The Kiss, it was directed by William Heise for Thomas Edison, who also happens to be credited (wrongfully, according to some) for the invention of the electric lightbulb. Notably, a lesser known work produced by Edison the year before, The Dickson Experimental Sound Film, is widely credited as being the first suggestion of homosexuality on film. The film is commonly labeled online and cited in at least three publications as “The Gay Brothers”.

Filip Vest, Bemærkninger. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

Filip Vest, Bemærkninger (screenshot).

Filip Vest, Bemærkninger (screenshot).

68 years later, in 1963, the artist Andy Warhol as part of his foray into the cinematic medium made the 50-minute silent film Kiss. Depicting both opposite- and same-sex ‘kissers’, the film positions itself within Warhol’s oeuvre as part of his use of celluloid film to explore and reveal his erotic desires and voyeuristic tendencies. Warhol notoriously performed his artistic persona as asexual for the majority of his career, enabling him to move fluently between agents of subculture and transgression and conservative wealthy art patrons. This apolitical position didn’t get him in trouble until it was challenged by his artistic peers and gay activists when the AIDS crisis emerged in the US. In parallell with the increasingly emancipatory narratives being depicted in cinematic film in the 1960s and 1970s, Warhol staged his subjects and filmed them in situations where the line between clinical observation to something just short of pornography blurred.

Less concerned with pointing out and challenging societal norms and scripting transgressive behaviour than the “king of filth” John Waters, Warhol’s Kiss is perhaps most notable for how it projects a contemporary longing through a nostalgic lens. Rather than the cinematic rebellions of his queer artistic contemporaries, which included Waters, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luis Buñuel, Luchino Visconti, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Warhol approaches intimacy with a camera lens much more like The Kiss of 1896, straight-on, without emotion or desire to self-represent. However, only a year later, Warhol would go on to make Blow Job, another silent film which depicts the sexual act with a one-shot of the face of a man (allegedly) receiving fellatio, placing him more firmly in a time when cinemas existed both for consumption of Hollywood studio fare, auteur cinema led by European directors and studios, and pornography. Cinemas were, in gay culture, also a known site for cruising. Warhol’s Blow Job is more interested in the dynamics of a peep show than in narrative cinema. When watched, it facilitates a welcome reminder of the potency of our imagining of action outside of the frame. What lies outside of the frame is of course us, a carrier-bag of non-endings and “main character” syndrome. If cinemas were less socially restrictive, we would probably always be engaging in acts of desire and self-narrated suspense in these darkened rooms. (1)

Filip Vest, Filmkys performance. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

Filip Vest, Filmkys performance. Foyer Contemporary. Photo: Lisbeth Holten.

As the AIDS epidemic took hold of the lives of queer communities and the cultural imagination of the Western world, queer artists channeled both activism, rage, and mourning through their art. The British director and artist Derek Jarman became renowned in the 1970s and early 1980s for his artistic and pulp films, such as his feature film debut Sebastiane from 1976 which portrays the torture and death of the historically Christian martyr as driven by homoerotic tension, and alludes to BDSM. Jarman, who in the 1980s shifted into more mainstream cinematic distribution and recognition, was due to AIDS-related illnesses and partial blindness forced back to the cinematic fray for his final film, Blue, in 1993. Since the director’s eyesight had dilapidated to the extent in which he could only see certain shades of blue, consists of a single shot of saturated blue colour – specifically International Klein Blue (RGB 0, 47, 167, CMYK 100, 72, 0, 35), as the soundtrack where Jarman and some of his long-time collaborators' voices describe his life and vision. As viewers, our somewhat perverse desire to witness the artist’s martyr-like death on screen is met and challenged, a resolute but compassionate final gesture from an artist who dedicated his career to challenging normative depictions of artistry and desire.

We are left to imagine Jarman’s death off-screen, his impending absence relayed to us in devastating monochrome, a reminder that as much as cinematic images can imprint on us, the projection of our own experiences onto them play a decisive role in their signification.

(1) A sidenote, comparison, and instruction on the satisfactions of kissing and cinema-going: Recently, I witnessed an acclaimed Norwegian, gay filmmaker sharing an anecdote of his first kiss with another boy in a cinema. He said that however much he enjoyed it and found it a culmination of years of desire, he also left annoyed that he had missed crucial plot developments in Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece Stalker (1979), and bought a ticket for a second screening, this time alone.

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Celsius Projects. Photo: Lena Bergendahl.

3rd score: Fuck Roger Rabbit, Who Framed Betty Boop?

As the same political body seeks to impose cruel, invasive and violent regulations on women’s health and gender non-conforming bodies in the US, it is notable that the enaction of the Hays Code was made possible by a United States Supreme Court ruling that films did not have First Amendment protection (concerning the freedom of speech), due to the film industry being a business that could be easily used for "evil", and several local governments passed laws restricting the public exhibition of "indecent" or "immoral" films. “With the Hays Code, one of the things the film industry just assumed was that its audience was white and straight and only white, straight males (...) They would do things that appealed to that audience base, really” says Australian film curator Chelsey O’Brien in a 2021 interview.

“When you think about characters like Betty Boop, who started out as this incredible flapper who was sexually unrestricted and incredibly interesting, but later due to the Code goes on to become this sort of conservative house wife figure”. Since the Hollywood studio complex has held a firm grasp on our collective imagination of romance and the consumption of it for a century now, it is worth considering what we have gained, if anything, and what we have lost, if not everything, to projecting our desires onto film. And as cinemas are the rooms in which these fantasies have, until the last decade, majorly played out, it is worth re-considering their function as a space of congregation and potential intimacy as well. Celluloid film and the cinema as a social context was for the majority of the 20th century considered a powerful enough medium to sway populations through the production of propaganda films, so why should we not presume the extent of its effect on how it affects our imagination and enactment of our desires?

As gender and queer theory reaches backwards in history to bring the lost expatriates of art and cultural forms of expression home, it is in equal measure heartening, devastating and obvious to realise how, as antiquity has been misused to construct a Euro-centric history of civilisation, Hollywood has contributed to the warping of our desires and the regulation of narratives which portray any form of consensual sexual dissent, be it homosexuality, bisexuality, kink, unprotected sex, sex as teenagers, sex as elderly people, sex work, and more, as a one-way road to death and on the way there, social stigmatisation and exclusion.

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Celsius Projects. Photo: Lena Bergendahl.

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Celsius Projects. Photo: Lena Bergendahl.

Today, academics, screen culture researchers, artists and art students, writers and critics are leading a collective effort to reinstate the BIPOC, queer and non-conforming persons who helped establish early cinema and to open up the language of cinema through analyses of “code-switching” or “-stretching”. As a suggestion for a direct action to accompany this shift and the “queering” of cinematic history, the question of whether to reclaim some of the intimacy which was ingrained in early cinema as a space for collective imagination and consumption can, or should, make a return.

The stories of first kisses and transgressive behaviours in cinemas, which the medium itself often depicts and in effect perpetuates as a space to enact desire, are multifold, so why not look at cinema’s inherent architectural logic and see it as something akin to a club dark room or imagine its future as the transposition of church buildings in the Danish capital Copenhagen to more secular venues for social services and cultural activity. The cinema, as a dark room, gives us the leniency to enact or imagine our desires without identifying ourselves fully, to project them onto others and/or to take on the role of voyeur. I was recently in an empty cinema stripped of its more decorative elements and it was more readily available to host a rave than a movie screening. As the Hollywood studio complex reinvents itself in our pockets, why don’t we appropriate the architectural spaces it leaves behind?

Filip Vest, Filmkys. Celsius Projects. Photo: Lena Bergendahl.

In the article ‘What The History Of Kissing In Film Can Tell Us About Ourselves, According To The Experts’, entertainment journalist Ivana Rihter writes: “Kissing is an art, and like all art forms, the dominant style changes across eras. In movies especially, there are the classics, the rebels and the anomalies that happened ahead of their time.” To imagine the future of cinema we can as with most art-forms look to its origins for indicators on its potential before major monetary and regulatory interests came to dominate it. In assessing it as a recorded history of the regulation, and in some cases invention, of depictions of desire in mainstream culture, we can use this knowledge to articulate demands to cinema’s future, not just in terms of representation on screen, but a deregulation of our desires. And as the kissing scene in ‘Notorious’ shows us, the sum of a larger transgression can be constructed cautiously, sometimes only three seconds at a time.

(As history leans in) Close your eyes, wet your lips, and count.

FILIP VEST "FILMKYS"

October 26, 2022 – January 15, 2023

FOYER Contemporary (PARK Bio)

Østerbrogade 79, 2100 Copenhagen

Håkon Traaseth Lillegraven (f. 1992) er kurator, kunstformidler og skribent, uddannet i kunsthistorie og kuratering ved Central Saint Martins i London.